Practice point

Beta-lactam allergy in the paediatric population

Posted: Jan 30, 2020

Principal author(s)

Tiffany Wong, Adelle Atkinson, Geert t’Jong, Michael J. Rieder, Edmond S. Chan, Elissa M. Abrams; Canadian Paediatric Society, Allergy Section

Paediatr Child Health 2020 25(1):62. (Abstract)

Abstract

Beta-lactam allergy is commonly diagnosed in paediatric patients, but over 90% of individuals reporting this allergy are able to tolerate the medications prescribed after evaluation by an allergist. Beta-lactam allergy labels are associated with negative clinical and administrative outcomes, including use of less desirable alternative antibiotics, longer hospitalizations, increasing antibiotic-resistant infections, and greater medical costs. Also, children with true IgE-mediated allergy to penicillin medications are often advised to avoid all beta-lactam antibiotics, including cephalosporins, which is likely unnecessary in greater than 97% of those reporting penicillin allergies. Most patients can be safely treated with penicillin or amoxicillin if they do not have a history compatible with IgE-mediated or systemic, delayed reactions such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), serum sickness-like reactions, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, or acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). Guidance is provided on how to stratify risk of beta-lactam allergy, and on test dosing and monitoring in the outpatient setting for patients deemed low risk. Guidance for patients at higher risk of beta-lactam allergy includes criteria for appropriate referral to allergists and the use of alternative antimicrobials, such as cephalosporins, while awaiting specialist assessment.

Keywords: Beta-lactam; Challenge; Drug allergy; Penicillin

Background

Definition and categorization of beta-lactam allergy

The World Health Organization defines drug allergy as immunologically mediated drug hypersensitivity reactions [1]. Drug allergies have historically been categorized by the Gell and Coombs system of hypersensitivity (Table 1). Clinically, drug allergies are usually classified as immediate (typically occurring within 1 hour) or non-immediate (occurring after 1 hour, but often days or weeks later) after medication initiation. Only IgE-mediated drug allergy falls into the immediate category.

Type I reactions, though rare, are concerning for many patients and practitioners. They are unlikely to occur with the first course because exposure is required before sensitization can occur [2]. Anaphylactic reactions to penicillin medications are rare, having been reported in <1% of children and young adults. Parenteral, long-term (and, particularly, high-dose) therapy increases risk for developing beta-lactam allergy compared with oral, intermittent therapy. A family history of beta-lactam allergy has not been shown to increase the risk in individuals [2].

Although maculopapular exanthems associated with beta-lactams are believed to be true type IV allergy in about 5% of adults, they are far less common—and have been estimated to affect less than 2%—of children. Most maculopapular exanthems in children are caused by infection and do not contraindicate further use of antibiotics [2][3].

Epidemiology

Beta-lactam allergy is reported in 5% to 8% of children in North America and Europe [4]. In paediatric patients labelled with beta-lactam allergy and referred to an allergist, 94% to 96% tolerate beta-lactam challenges upon further evaluation [3][5].

Paediatric patients labelled as having a beta-lactam allergy are often misdiagnosed due to misclassification of symptoms of illness or common side effects of antibiotic medications. An interaction between the antibiotic and a pathogen can sometimes mimic an allergic reaction [6]. Circulating beta-lactam-specific IgE antibodies can decrease naturally over time [7]. However, many patients are never reassessed and continue to carry this label.

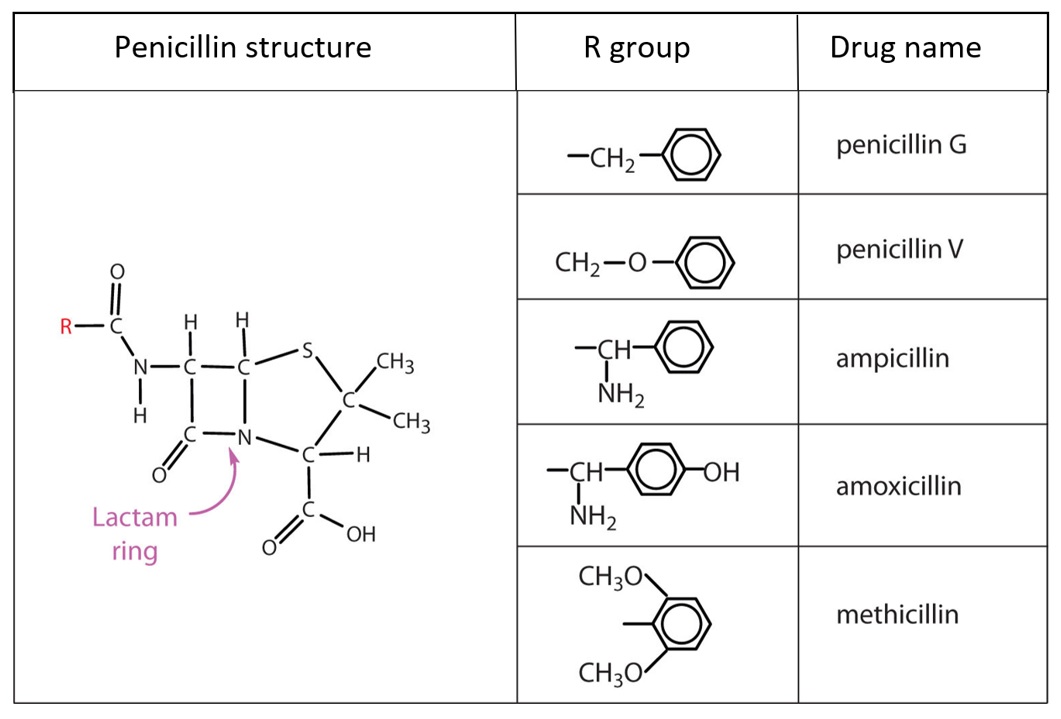

Beta-lactam structure and properties

Beta-lactam antibiotics (penicillins and cephalosporins) share a beta-lactam ring. Medications differ based on the different R groups on the acyl side chain (Figure 1). Beta-lactam antibiotics develop allergenic potential when the beta-lactam ring opens and links with nearby proteins in the blood.

| Figure 1 |

|

| Source: Seetaram Swamy S. Penicillins, slide 13: www.slideshare.net/seetaram443/penicillins-53561419 |

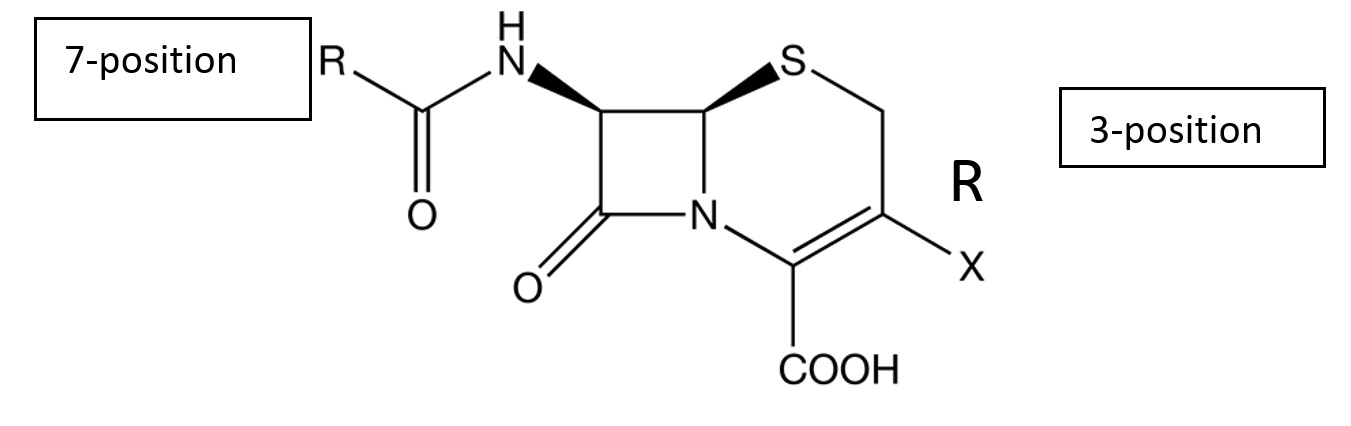

| Figure 2. Cephalosporin structure |

|

Cross-reactivity among beta-lactam antibiotics in allergic individuals

Cross-reactivity among the penicillins is caused primarily by similarities in their core ring structure and their side chains. Cross-reactivity cannot be determined by side-chain similarities alone. When a patient has a true allergy to a penicillin, all penicillins should be avoided.

It was previously believed that cephalosporin allergy occurred in 10% to 20% of penicillin-allergic individuals, and that they should avoid all cephalosporins. However, it is now understood that this occurrence rate was an overestimation, and that associated precautions were overly restrictive. Although these medications share a common beta-lactam ring (Figure 2), evidence has shown that it is rarely the structure implicated in allergy [2]. All early cases reported were in patients who received first-generation medications. Pre-1980 cephalosporins were found to be contaminated with penicillin, and these early reactions are now known to have been caused primarily by structurally similar side chains (Tables 2 and 3). For example, when an individual has a confirmed allergy to amoxicillin, they are likely to react to cephalexin as well because of the group 2 side chain at position 7. The true rate of cross-reactivity is thought to be about 2% [2]. With the true incidence of penicillin allergy among patients who report a history being at or under 10%, the rate of cross-reactivity is now estimated to be less than 1% in patients with self-reported, but unconfirmed, allergy.

Assessing beta-lactam allergy: An overview

Detailed history-taking is critical to the evaluation of possible beta-lactam allergy, the level of patient risk, and for deciding whether skin testing or an oral challenge is indicated. Individuals should be assessed and examined by a physician while they are experiencing a suspected reaction, if possible. Investigations will depend on the nature of the suspected reaction.

|

Important questions on history after a suspected reaction

|

Epicutaneous and intradermal testing

Epicutaneous and intradermal testing with validated and standardized penicillin reagents is recommended by international guidelines for the assessment of suspected IgE-mediated allergy. Although the negative predictive value of skin testing for penicillin allergy in adults approaches 100%, one recent Canadian study showed the predictive value of penicillin skin testing in children to be poor, with a negative test in 94% of children who had a positive oral challenge [5]. Thus, skin testing is less likely to be useful in children than in adults. Skin testing is not a useful test for screening of allergy where there is no history of a convincing reaction because the positive predictive value for penicillin allergy has been reported to be as low as 40% [2].

Provocative drug challenge

The gold standard test to rule out an IgE-mediated allergy is a drug challenge test, conducted when, after thorough history taking +/- skin testing, an individual is deemed unlikely to be allergic. Skin testing with standardized reagents is specific to penicillin and does not necessarily rule out allergy to other penicillin group members with different side chains (e.g., amoxicillin). Thus, oral drug challenge to the specific medication is preferred. There is no international consensus on how challenge tests are to be conducted. Many Canadian centres provide a single dose challenge, whereas others provide graded dosing in two steps (i.e., 10% of the dose, followed by the remaining 90% 30 minutes later). Drug challenge tests in appropriately selected individuals are safe and effective, and recent data have indicated that going directly to oral challenge, without skin testing, is more reliable [5]. Drug challenge tests can be dangerous and are contraindicated if when a child’s history is consistent with recent anaphylaxis or systemic, non-immediate immunologic reaction (e.g., serum sickness-like reaction, SJS, DRESS syndrome, or drug-induced hemolytic anemia).

Clinical implications of erroneous beta-lactam allergy labelling

A diagnosis of drug allergy in children should be made with special care because inaccurate penicillin allergy labelling is associated with negative clinical and administrative outcomes. Second-line non-beta-lactam antimicrobials are generally inferior for infection management and have been associated with prolonging hospital stays, higher admission rates for intensive care, readmissions, and mortality. As a result of increased alternative, broad-spectrum antibiotic use, antibiotic resistance is expanding and now includes vancomycin-resistant enterococcus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) as well as higher rates of C. difficile infections. Rising health care costs around the world are due in part to higher antibiotic costs per hospitalization and prolonged hospital stays. Removal of erroneous penicillin allergy labels has been shown to mitigate both trends [10]. Penicillin allergy de-labelling programs have become a key strategy of antimicrobial stewardship programs in North America.

Figure 3 has been evaluated by paediatric allergists, an antimicrobial stewardship pharmacist, a general paediatrician, and paediatric infectious disease specialists. Just over 60% of subjects found to be non-allergic by an allergist on the same day as their clinic appointment could have been identified as low-risk based on history alone, using the questionnaire and following this algorithm. No patient identified as low risk was later diagnosed as allergic by an allergist, which demonstrates the safety and reliability of this clinical tool.

Figure 3: Algorithm to identify paediatric patients at low risk for penicillin allergy is available as a supplementary file.

Guiding principles for beta-lactam allergy in the paediatric population

Individuals with a history of suspected penicillin reaction but who have since tolerated one course of the medication are not allergic. These antibiotics can be prescribed again without monitoring dose administration.

Individuals at low risk for penicillin allergy can safely have the medication prescribed again. Mild, delayed exanthems do not contraindicate further use of these antibiotics. Administration of a single test dose of amoxicillin (15 mg/kg) with a 1-hour observation period can provide reassurance and confirm that no allergy is present. These individuals can be prescribed cephalosporins (with similar and dissimilar side chains), carbapenems, and monobactams, without monitoring dose administration.

Individuals with suspected IgE-mediated allergy should not be prescribed penicillin. They must be referred to a paediatric allergist for assessment. For individuals with suspected IgE-mediated allergy, avoid prescribing cephalosporins with similar side chains. Cephalosporin medications with dissimilar side chains can be prescribed. When necessary (e.g., for patients who require frequent antibiotics for a chronic disease), or when a certain cephalosporin is desirable, a provocative challenge to the specific cephalosporin a treatment team would like to use, can be conducted.

Individuals who have experienced severe systemic or cutaneous delayed adverse reactions following a dose of penicillin, should not be prescribed this antibiotic in the future. They must be referred to a paediatric allergist for assessment and counselling. There is no robust evidence to indicate cross-reactivity between specific penicillins or penicillins and cephalosporins with similar side chains in severe delayed allergic reactions. Future decisions for penicillin use other than the ones implicated should be based on benefit versus risk assessment on a case-by-case basis. Some organizations recommend avoiding cephalosporins with similar side chains in such cases [11].

Individuals who have been diagnosed with penicillin allergy by an allergist should be re-assessed by a paediatric allergist after 5 years. This allergy can be outgrown and avoiding penicillin for life may not be necessary.

Acknowledgements

This practice point was reviewed by the Community Paediatrics and Infectious Disease and Immunization Committees of the Canadian Paediatric Society, and co-authored by two members of the CPS Drug Therapy and Hazardous Substances Committee, Drs. Geert t’Jong and Michael J. Rieder.

CANADIAN PAEDIATRIC SOCIETY ALLERGY SECTION

Executive members: Elissa M. Abrams MD (President), Edmond S. Chan MD (Secretary-Treasurer)

Principal authors: Tiffany Wong MD, Adelle Atkinson MD, Geert t’Jong MD, Michael J. Rieder MD, Edmond S. Chan MD, Elissa M. Abrams MD

References

- Johansson SG, Bieber T, Dahl R, et al. Revised nomenclature for allergy for global use: Report of the Nomenclature Review Committee of the World Allergy Organization, October 2003. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;113(5):832–36.

- Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters; American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Drug allergy: An updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2010;105(4):259-73.

- Abrams EM, Wakeman A, Gerstner TV, Warrington RJ, Singer AG. Prevalence of beta-lactam allergy: A retrospective chart review of drug allergy assessment in a predominantly pediatric population. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2016;12:59

- Gomes ER, Brokow K, Kuyucu S, et al. Drug hypersensitivity in children: Report from the pediatric task force of the EAACI Drug Allergy Interest Group. Allergy 2016;71(2):149-61

- Mill C, Primeau MN, Medoff E, et al. Assessing the diagnostic properties of a graded oral provocation challenge for the diagnosis of immediate and nonimmediate reactions to amoxicillin in children. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170(6):e160033.

- Pichler WJ. Delayed drug hypersensitivity reactions. Ann Intern Med 2003:139(8):683-93.

- Blanca M, Torres MJ, Garcia JJ, et al. Natural evolution of skin test sensitivity in patients allergic to beta-lactam antibiotics. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999;103(5 Pt 1):918-24.

- Pichichero ME. A review of evidence supporting the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendation for prescribing cephalosporin antibiotics for penicillin-allergic patients. Pediatrics 2005;115(4):1048-57.

- Macy E, Contreras R. Health care use and serious infection prevalence associated with beta-lactam “allergy” in hospitalized patients: A cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;133:790e796

- Trubiano JA, Thursky KA, Stewardson AJ, et al. Impact of an integrated antibiotic allergy testing program on antimicrobial stewardship: a multi-center evaluation. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65(1):166-74.

- Government of Quebec, Institut national d’excellence en santé et en services sociaux. Avis sur la standardisation des pratiques relatives aux allergies aux bêta-lactamines. June 2017: https://www.inesss.qc.ca/nc/en/publications/publications/publication/avis-sur-la-standardisation-des-pratiques-relatives-aux-allergies-aux-beta-lactamines-modification.html (Accessed August 15, 2019).

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this position statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. Internet addresses are current at time of publication.

Last updated: Feb 8, 2024