Practice point

Comprehensive sexual health assessments for adolescents

Posted: Dec 7, 2020

Principal author(s)

Natasha Johnson; Canadian Paediatric Society, Adolescent Health Committee

Paediatr Child Health 2020 25(8):551. (Abstract).

Abstract

Sexual activity and experimentation are normative parts of adolescent development that may, at the same time, be associated with adverse health outcomes, including the acquisition of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), unplanned pregnancy, and teen dating violence (TDV). Anticipatory guidance regarding sexual and reproductive health (SRH) for teens should address normal sexual development issues, such as identity and attractions, safe relationships, safer sex, and contraception. Health care providers (HCPs) can enhance the sexual education of the youth they see and help mitigate negative health outcomes. This practice point offers a ‘7-P’ approach to ensure that HCPs obtain comprehensive sexual health assessments for adolescents. Teen issues such as identity, confidentiality and consent, and dating violence are discussed, and Canadian Paediatric Society resources are cited to provide more detailed care pathways on related issues: contraception, pregnancy, and STIs.

Keywords: Adolescents; Sexual and reproductive health; Sexually transmitted infections; Teens

Setting the stage for a conversation about sexual health

Health care providers (HCPs) are uniquely positioned to provide education for adolescents they see in practice and help improve their sexual and reproductive health (SRH). Adolescents are unlikely to reveal SRH concerns without prompting and may not seek care unless confidentiality is assured [1]-[5]. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC’s) framework for SRH has been adapted here to ‘7 Ps’: an approach to assessment covering the following topics: Partners, Practices, Protection from sexually transmitted infections (STIs), Past history of STIs, Prevention of pregnancy, Permission (consent), and Personal (gender) identity [6]. SRH is an essential component of care for all adolescents, including those with developmental disabilities and chronic health conditions, who may be as sexually experienced as their peers [7][8].

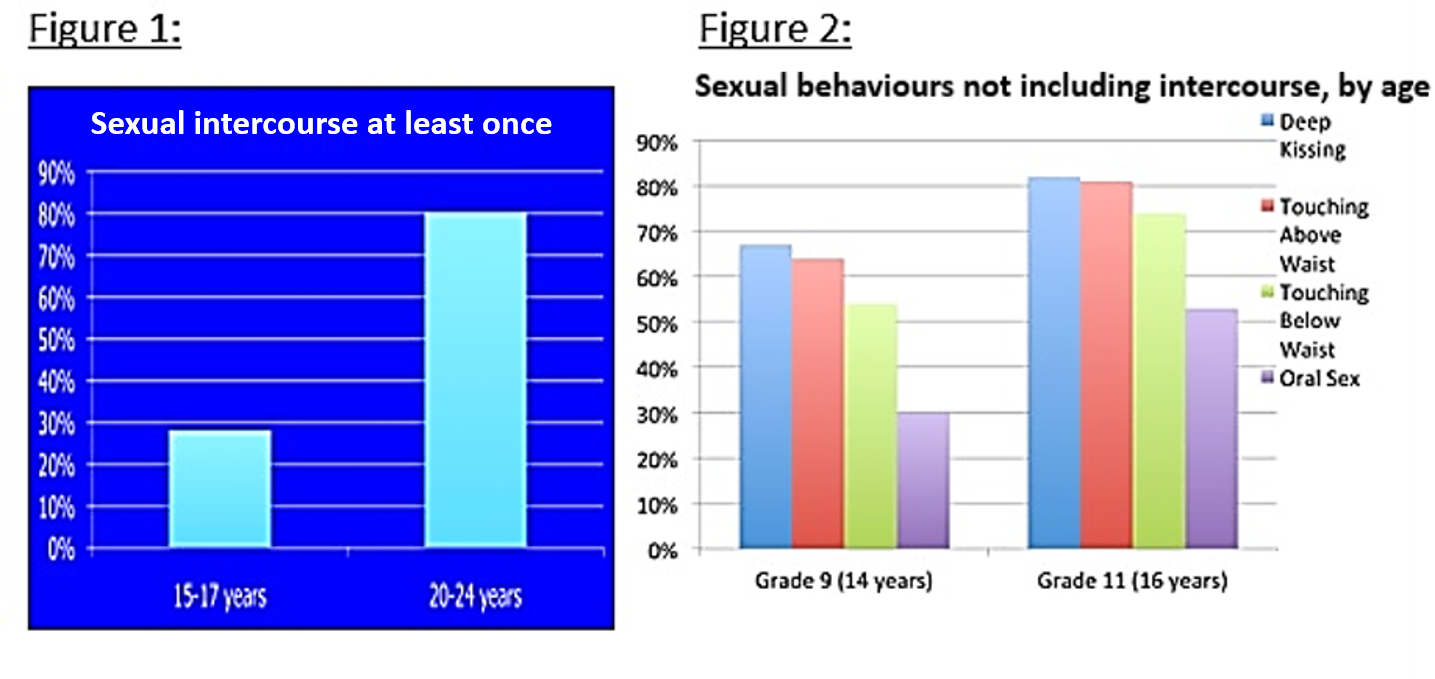

Canadian data suggest that roughly 30% of adolescents aged 15 to 17 years have had penile-vaginal sex at least once (Figure 1). While only 10% of males and 8% of females report first genital intercourse occurring before age 15 years [9][10], adolescents may engage in sexual activities apart from penile-vaginal intercourse, such as masturbation, digital sex, oral sex, and anal intercourse (Figure 2) [11]. Also, expressed sexual attraction may not always align with a person’s sexual practices. For this reason, asking questions about specific types of sexual behaviours, regardless of orientation, enables HCPs to offer anticipatory guidance and screening.

Pregnancy

The timing of last menstrual period (LMP) must be assessed for all sexually active teens. A pregnancy test should be offered when LMP precedes a health encounter by more than 4 weeks or when the teen seems unsure of the date. When a pregnancy test is positive, HCPs should counsel on options or refer to a clinician who can offer timely counselling. For teens who are wishing to avoid pregnancy, contraceptive needs should be discussed. In addition to consistent condom use, recommended methods of birth control are discussed in this CPS statement: Contraceptive care for Canadian youth [12]. Consider supplying latex condoms in your clinical space at no cost.

For teens who are ambivalent about contraception or considering pregnancy, a multivitamin containing folic acid should be recommended. Also, optimal immunization with measles-mumps-rubella (MMR), varicella, and hepatitis B vaccines should be ensured. Two CPS documents, Meeting the needs of adolescent parents and their children and Adolescent pregnancy, are helpful resources for HCPs protecting teen pregnancies.

LGBTQ+ youth

LGBTQ+ youth include those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, two-spirit, queer, questioning, intersex, or non-binary. LGBTQ+ youth are at increased risk for adverse health issues, such as STI acquisition, bullying, depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, substance use, suicide attempts, and insecure housing [13][14]. Transgender individuals have increased rates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts compared with cisgender individuals (those whose gender identity matches their sex assigned at birth) [15]. Parental support of sexual orientation and gender identity as well as timely access to gender-affirming treatments are important protective factors [16][17]. Numerous barriers exist for LGBTQ+ youth to access health care [18]. Offering an inclusive, open, and welcoming space where no-one makes assumptions about identities, attractions, or sexual behaviours is an important component of care.

STIs

STIs can be transmitted via digital, oral, genital, or anal sexual contact. Adolescents are a high-risk group for STIs, both for biological and behavioural reasons [19]-[25]. Risk factors are numerous (Table 1). Knowledge of local epidemiology patterns will inform screening practice recommendations. Refer to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) for Canadian data [19].

|

Table 1. Risk factors for STIs

|

|

| Any sexually active youth < 25 years old | |

|

|

|

Adapted from reference [19]

|

|

STIs (including chlamydia and gonorrhea) are often asymptomatic. Asymptomatic teens can readily believe themselves to be uninfected. Other infections that can affect teens without symptoms, or where primary symptoms are easily or often missed, include human papillomavirus (HPV), syphilis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis, and genital herpes. When they are symptomatic, STIs can present in non-specific ways, as conjunctivitis, rash, dysuria, inguinal adenopathy, ulcer, vaginal or urethral discharge, prostatitis, or with anal or pharyngeal symptoms. In sexually active females or trans males, irregular vaginal bleeding or undifferentiated abdominal pain may be the presenting symptom.

Complications of untreated STIs include pelvic inflammatory disease, prostatitis, chronic pelvic pain, infertility, and effects on a developing fetus or neonate. ALL sexually active youth under 25 years of age should be offered annual screening (Table 2). Additional risk factors (e.g., the mention of a new partner) should increase frequency of screening. For immunodeficient or symptomatic adolescents, additional testing is recommended [19]. Clinicians should remember to screen for STIs even though Pap testing and routine pelvic exams are no longer recommended for sexually active teens [26]. Routine screening has been facilitated by new technologies, such as nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) on urine for any sexually active teen, and self-collected vaginal swabs (see Diagnosis and management of sexually transmitted infections in adolescents ) [27].

HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is an intervention that reduces HIV transmission in high-risk populations. PrEP involves prescribing long-term, daily antiretroviral medication for individuals before they become exposed to HIV, to reduce risk of acquisition [28]. HIV post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) involves taking antiretroviral medication to prevent HIV seroconversion after high-risk exposure has occurred. Treatment decisions regarding use of PEP and PrEP and HIV treatment must be made collaboratively, in consultation with an infectious disease specialist in HIV or a health care team with expertise [21].

|

Table 2. Recommended STI screening for asymptomatic immunocompetent youth

|

||

| Specimens | Testing | Population to test |

|

First catch urine*

(*refers to first part of urinary stream)

OR

Urethral or cervical swab

OR

Vaginal swab (may be self-collected)

|

NAAT for:

Chalmydia trachomatis

AND

Neisseria Gonorrhoeae

(NG)

|

All sexually active youth<25 years

|

|

Pharyngeal swab

|

Culture for Chlamydia and NG

(and/or NAAT if available in local lab)

|

Those who have performed oral sex

|

|

Anal swab

Insert swab 2 to 3 cm into the anal canal, press laterally to sample epithelium. If visible fecal contamination, discard the swab and obtain another

|

Culture for Chlamydia and NG

(and/or NAAT if available in local lab)

|

Those who report anal receptive intercourse (including MSM)

|

|

Serology

|

Syphilis serology HIV serology

|

All sexually active youth

|

|

Consider serology

|

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis A

Hepatitic C

|

All sexually active youth <25 years with no or uncertain vaccination history

Particularly if oral/anal contact

If personal or partner history of IV drug use

|

|

Cervix

Papanicolaou (Pap) smear

|

Liquid-based cytology

|

Varied age of initiation per provincial/territorial guidelines – not before age 21 years (applies to females as well as trans males with intact cervixes)

|

|

• STI screening should be conducted with informed consent. A special consent form for HIV testing is not necessary. The PHAC recommends against using “cumbersome forms” that may be a barrier to testing.

• Screening for HIV and syphilis should be done using an “opt-out” approach prefaced by the following: “Urine and blood testing are part of the routine screening that we offer to all sexually active teens. Even though the risk of HIV and syphilis may be low, treatments are available, and so it is important to identify infections that may be there even without symptoms. Is this ok with you?”

|

The HCP offering screening should inform the teen that they may be contacted by public health in the event of a positive screen, communicate positive STI results promptly, and provide treatment to the patient, and to partners when possible.

The HCP should also review immunization history to ensure that teens with an STI are up-to-date for the following vaccines: HPV, hepatitis A and B (for men having sex with men (MSM) and others having anal sex), varicella, and MMR (for pregnancy implications). They must arrange for catch-up vaccines or doses when needed.

While no barrier method is 100% effective against STI transmission, latex condoms offer the best protection available for sexually active youth. Spermicide-coated condoms can promote STI transmission and should be avoided. For teens with latex allergy, polyurethane or polyisoprene condoms should be recommended despite increased likelihood of breakage [29]. Dental dams (latex or polyurethane sheets) can reduce STI transmission between mouth and vagina or anus.

Sexual consent laws and other legal considerations

In 2008, Canadian legislation increased the age of consent for non-exploitative sexual activity to 16 years of age. There are “close in age” exceptions to the law (Table 3) [30][31]. Discussion with your local Child Protection Agency (CPA) is recommended when there is a concern or advice is needed.

Early age of initiation of sexual activity should prompt HCPs to consider sexual abuse or assault. Clinicians have a duty to report suspected sexual abuse or exploitation of children (although reporting age varies among provinces/territories).

Sexting is another issue with possible legal implications that should be addressed with youth. Teens can be convicted for possessing and distributing child pornography, even when the picture they are sending is of themselves [32].

|

Table 3. Age of consent for sexual activity in Canada

|

||||

|

Under 12 years

|

12 to 13 years

|

14 to 15 years

|

16 years

|

Under 18 years

|

|

Cannot consent to any sexual activity

|

Can consent to non-exploitative sex as long as age difference does not exceed 2 years

|

Can consent to non-exploitative sex as long as age difference does not exceed 5 years

|

Can consent to non-exploitative sex

|

Cannot consent to exploitative sex, e.g.:

|

Teen dating violence

Teen dating violence (TDV) is “physical, sexual, psychological, or emotional violence within a dating relationship, including stalking”. TDV can occur in-person or electronically, and might involve a current or former dating partner [33]. One U.S. study reported 21% of dating females and 10% of dating males as having experienced TDV [34]. TDV is associated with depression, anxiety, substance use, antisocial behaviours, suicidal ideation, and higher risk for TDV later in life. Intoxication with substances (alcohol in particular) is associated with sexual assault [35]. Consider referral to local crisis or sexual assault team in cases of TDV.

Summary

SRH is an essential component of care for all adolescents (Table 4). Using a ‘7 Ps’ approach to ensure comprehensive sexual health assessment is recommended. Creating a positive and inclusive space will welcome ALL youth, including those who are members of the LGBTQ+ community. All sexually active youth younger than age 25 should be screened annually for STIs. Comprehensive sexual health visits can improve the overall health of adolescents. HCPs should routinely initiate discussions about SRH, dispel myths, address contraceptive needs, offer STI screening and treatment, screen for safe relationships, and administer relevant vaccines.

|

Table 4. Overview of comprehensive sexual and reproductive health assessment

|

|

Inclusive, welcoming space (no assumptions)

|

|

Confidentiality (and limits) reviewed with teen

|

|

‘7 Ps’ approach to sexual and reproductive health *

Partners

Practices

Protection from STIs

Past history of STIs

Prevention of pregnancy

Permission (consent)

Personal identity (gender identity)

|

|

Consider pregnancy test when LMP is more than 4 weeks earlier

Options counselling in the event of positive test

|

|

STI screen for all sexually active youth younger than 25 years (Table 2)

At least annually – more often when risk factors for STIs are present (Table 1)

|

|

Recommend condom use to all sexually active youth

Preferably latex, without spermicide

Polyurethane or polyisoprene condoms in cases of latex-allergy

(consider having a supply to offer at no cost in your clinical space)

|

|

Discuss contraceptive options

|

|

Review indications for emergency contraception

(consider having some types freely accessible in your clinical space)

|

|

Ensure relevant vaccines are up-to-date

(HPV, hepatitis A and B, varicella, MMR)

|

|

Consider PEP or PrEP in consultation with an expert in HIV prophylaxis and treatment

If risk for HIV transmission is high

If risk for hep B transmission is high and a teen is unvaccinated or non-immune

|

|

Be aware of sexual consent laws (Table 3)

Consult with your local child protective agencies, as necessary

|

|

Assess relationship safety

Consent, teen dating violence, sexting

|

|

Arrange follow-up

When STI screen test is positive, advise teens that they may be contacted by Public Health

In the event of a positive screen, treat patient and partner(s)

|

|

HIV human immunodeficiency virus; HPV human papillomavirus LMP last menstrual period; MMR measles mumps rubella; PEP post-exposure prophylaxis; PrEP pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI Sexually transmitted infection

|

|

*The ‘7 Ps’ have been adapted from reference [6]

|

Recommended resources

- STI Canada App

- www.sexandu.ca

- IUC Expert App

- Safer sex resource for teens: https://www.optionsforsexualhealth.org/sexual-health/sexually-transmitted-infections/safer-sex-tips

Acknowledgements

This practice point has been reviewed by the Community Paediatrics and Infectious Diseases and Immunization Committees of the Canadian Paediatric Society.

CANADIAN PAEDIATRIC SOCIETY ADOLESCENT HEALTH COMMITTEE

Members: Holly Agostino MD, Marian Coret MD (Resident Member), Karen Leis MD (Board Representative), Alene Toulany MD, Ashley Vandermorris MD, Ellie Vyver MD (Chair)

Liaisons: Megan Harrison MD (CPS Adolescent Health Section)

Principal author: Natasha Johnson MD

References

- Salam RA, Faqqah A, Sajjad N, et al. Improving adolescent sexual and reproductive health: A systematic review of potential interventions. J Adolesc Health 2016;59(4S):S11-S28.

- Lindberg LD, Maddow-Zimet I. Consequences of sex education on teen and young adult sexual behaviors and outcomes. J Adolesc Health 2012;51(4):332-8.

- Alexander SC, Fortenberry JD, Pollak KI, et al. Sexuality talk during adolescent health maintenance visits. JAMA Pediatr 2014;168(2):163-9.

- Donaldson AA, Lindberg LD, Ellen JM, Marcell AV. Receipt of sexual health information from parents, teachers, and healthcare providers by sexually experienced US adolescents. J Adoles Health 2013;53(2):235-40.

- Copen CE, Dittus PJ, Leichliter JS. Confidentiality concerns and sexual and reproductive health care among adolescents and young adults aged 15-25. NCHS Data Brief 2016;266:1-8.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A Guide to Taking a Sexual History. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/sexualhistory.pdf (Accessed June 10, 2020).

- Cheng MM, Udry JR. Sexual behaviors of physically disabled adolescents in the United States. J Adolesc Health 2002;31(1):48-58.

- Murphy N. Sexuality in children and adolescents with disabilities. Dev Med Child Neurol 2005;47(9):640-4.

- Chandra A, Martinez GM, Mosher WD, Abma JC, Jones J. Fertility, family planning, and reproductive health of US women: Data from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Vital Health Stat 2005;23(25):1-160.

- Rotermann M. Sex, condoms and STDs among young people. Health Rep 2005;16(3):39-45.

- Boyce W, Doherty M, Fortin C, MacKinnon D. Canadian Youth, Sexual Health and HIV/AIDS Study: Factors Influencing Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviours. Toronto, Ont: Council of Ministers of Education of Canada, 2003.

- Di Meglio G, Crowther C, Simms J; Canadian Paediatric Society, Adolescent Health Committee. Contraceptive care for Canadian youth. Paediatr Child Health 2018:23(4):271–7. www.cps.ca/en/documents/position/contraceptive-care.

- City of Toronto. 2013 Street Needs Assessment Survey: www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2013/cd/bgrd/backgroundfile-61365.pdf (Accessed June 10, 2020).

- Rainbow Health Ontario. Fact Sheet: Because LGBT Health Matters: https://www.rainbowhealthontario.ca/wp-content/uploads/woocommerce_uploads/2014/08/Sexual%20health1.pdf (Accessed June 10, 2020).

- Veale J, Saewyc E, Frohard-Dourlent H, Dobson S, Clark B; Canadian Trans Youth Health Survey Research Group. Being Safe, Being Me: Results of the Canadian Trans Youth Health Survey. Vancouver, B.C.: Stigma and Resilience Among Vulnerable Youth Centre, School of Nursing, University of British Columbia, 2015. https://apsc-saravyc.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2018/03/SARAVYC_Trans-Youth-Health-Report_EN_Final_Web2.pdf (Accessed June 10, 2020).

- Bouris A, Guilamo-Ramos V, Pickard A, et al. A systematic review of parental influences on the health and well-being of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: Time for a new public health research and practice agenda. J Prim Prev 2010;31(5-6):273–309.

- Travers R, Bauer G, Pyne J, Bradley K, Gale L, Papadimitriou M; Trans PULSE Project, Children’s Aid Society of Toronto, Delisle Youth Services. Impacts of Strong Parental Support for Trans Youth: A Report Prepared for Children’s Aid Society of Toronto and Delisle Youth Services. 2012. http://transpulseproject.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Impacts-of-Strong-Parental-Support-for-Trans-Youth-vFINAL.pdf (Accessed June 10, 2020).

- Albuquerque AG, de Lima Garcia C, da Silva Quirino G, et al. Access to health services by lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons: Systematic literature review. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2016;16:2.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/std-mts/sti-its/cgsti-ldcits/index-eng.php (Accessed June 10, 2020).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STSs): Data and Statistics: www.cdc.gov/std/stats08/trends.htm#f12 (Accessed June 10, 2020).

- Kleppa E, Holmen SD, Lillebø K, et al. Cervical ectopy: Associations with sexually transmitted infections and HIV; A cross-sectional study of high school students in rural South Africa. Sex Transm Infect 2015;91(2):124–9.

- Macneily AE, Afshar K. Circumcision and non-HIV sexually transmitted infections. Can Urol Assoc J 2011;5(1):58–9.

- Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: A randomised trial. Lancet 2007;369(9562):657-66.

- Auvert B, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Cutler E, et al. Effect of male circumcision on prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus in young men: Results of a randomized controlled trial conducted in Orange Farm, South Africa. J Infect Dis 2009;199(1):14-9.

- World Health Organization. Prevention and Treatment of HIV and Other Sexually Transmission Infections among Men Who Have Sex with Men and Transgender People: Recommendations for a public health approach. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2011.

- Dickinson J, Tsakonas E, Gorber SC, et al; Canadian Task Force on Preventative Health Care. Recommendations on Screening for Cervical Cancer. CMAJ 2013;185(1):35-45:https://www.cmaj.ca/content/cmaj/185/1/35.full.pdf (Accessed June 10, 2020).

- Top KA, Allen UD, MacDonald N; Canadian Pediatric Society, Infectious Diseases and Immunization Committee. Diagnosis and management of sexually transmitted infections in adolescents. Paediatr Child Health 2014:19(8):429-33; Updated on-line November 2019: https://cps.ca/en/documents/position/sexually-transmitted-infections.

- WHO. Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment and Care for Key Populations. 2016 Update: www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/keypopulations-2016/en/ (Accessed June 10, 2020).

- Black A, Guilbert E, Costescu D, et al; Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. Clinical Practice Guideline: Canadian Contraception Consensus (Part 2 of 4). J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2015:37(11):S1-S39

- Bellemare S. Age of consent for sexual activity in Canada. Paediatr Child Health 2008;13 (6):475. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2532909/ (Accessed June 10, 2020).

- Government of Canada, Department of Justice. Age of Consent to Sexual Activity. www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/other-autre/clp/faq.html (Accessed June 10, 2020).

- Katzman D; Canadian Paediatric Society, Adolescent Health Committee. Sexting: Keeping teens safe and responsible in a technologically savvy world. Paediatr Child Health 2010;15(1):41-2.

- Vagi KJ, Olsen EO, Basile KC, Vivolo-Kantor AM. Teen dating violence (physical and sexual) among US high school students: Findings from the 2013 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169(5):474-82.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Violence Prevention/Preventing Teen Dating Violence. www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/teendatingviolence/fastfact.html (Accessed August 4, 2020).

- Anderson LJ, Flynn A, Pilgrim JL. A global epidemiological perspective on the toxicology of drug-facilitated sexual assault: A systematic review. J Forensic Leg Med 2017;47:46-54.

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this position statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. Internet addresses are current at time of publication.

Last updated: Feb 8, 2024