Practice point

Lyme disease in Canada: Focus on children

Posted: Jul 28, 2020

Principal author(s)

Heather Onyett; Canadian Paediatric Society. Updated by: Jane McDonald, Nicole Le Saux, Infectious Diseases and Immunization Committee

Abstract

Lyme disease, the most common tick-borne infection in Canada and much of the United States, is caused by the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi. Peak incidence for Lyme disease is among children five to nine years of age and older adults (55 to 59 years of age). The bacteria are transmitted through the bite of infected black-legged ticks of the Ixodes species. The primary hosts of black-legged ticks are mice and other rodents, small mammals, birds (which are reservoirs for B burgdorferi) and white-tailed deer. Geographical distribution of Ixodes ticks is expanding in Canada and an increasing number of cases of Lyme disease are being reported. The present practice point reviews the epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, management and prevention of Lyme disease, with a focus on children.

Key Words: Black-legged tick; Borrelia burgdorferi; Erythema migrans; Post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome

Lyme disease (LD), a serious disease, is the most common tick-borne infection in Canada and the Northeastern to Midwestern United States, with cases also occurring (with less frequency) on the west coast. LD is caused by the bacteria spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, transmitted to humans through the bite of infected black-legged ticks: Ixodes scapularis in Eastern and Central Canada and Ixodes pacificus in British Columbia.[1]

The primary hosts (carriers) of black-legged ticks are mice and other small rodents, small mammals, birds (which are a reservoir for B burgdorferi) and white-tailed deer (Figure 1). Although dogs can contract LD and carry ticks into homes and yards, there is no evidence that they spread the infection directly to people.[2]

Peak incidence for LD is among children five to nine years of age and older adults (55 to 59 years of age), and many cases likely go unreported.[1] No relationship between treated maternal LD and abnormal pregnancies or disease in infants has been documented.[3] Although there is a theoretical risk, no case of infection has been linked to blood transfusion.[4]

Ticks cannot jump or fly. Instead, they climb and wait on tall grasses or shrubs for a potential host to brush against them. They then transfer to the host and seek an attachment site.[5] Immature ticks (nymphs) are responsible for most human LD infections because their very small size hinders detection.[1]

If a tick is found attached to or feeding on a child, remove it as soon as possible. Ticks can attach and feed for five days or longer (Figure 2). Removing a tick within 24 h to 36 h of its starting to feed is likely to prevent LD.[6]

|

Figure 1) The life cycle of black-legged ticks and Lyme disease. Reproduced with permission from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, USA): www.cdc.gov/ticks/life_cycle_and_hosts.html |

|

Figure 2) Female black-legged ticks in various stages of feeding. Note the change in size. Reproduced from reference 1 © All rights reserved. With permission from the Minister of Health, 2014 |

How prevalent is LD in Canada?

Black-legged tick populations are well established in parts of British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, and may be expanding. Migratory birds can bring infected ticks into nonendemic areas, and people may also become infected while travelling to other endemic areas in North America and Europe.[6] In 2009, LD became a nationally reportable disease. The number of reported cases has increased from 128 in 2009 to an estimated ≥500 in 2013.[1][7]

What are the clinical manifestations of LD?

Clinical manifestations are divided into early, localized (cutaneous) disease, and later (extracutaneous) disease.

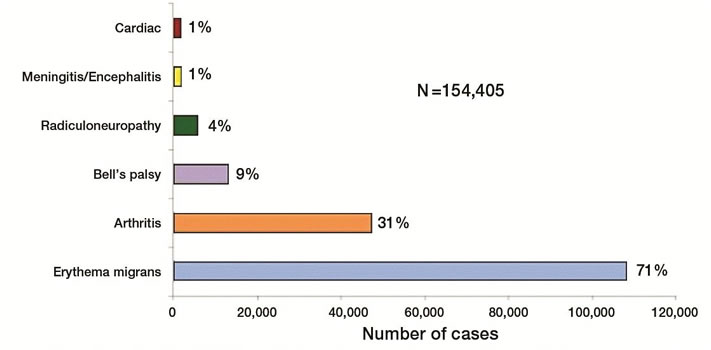

Early, localized (cutaneous) disease: Erythema migrans (EM) – a rash at the site of a recent tick bite – is the most common presentation in children and adults (Figures 3 and 4).[4][8] EM typically develops seven to 14 days (range three to 30 days) after a tick bite. EM is usually >5 cm and mainly flat. There may be central clearing or some bluish discoloration but a classic bull’s eye is uncommon. EM is usually asymptomatic (although it may produce a burning sensation) but is not painful to the touch, like a cellulitis. EM can be confused with a localized hypersensitivity reaction from a tick or insect bite, which is usually swollen, smaller in size and pruritic).[4] There can be either a single erythema migrans rash or multiple rashes without extracutaneous manifestations. However, fever, malaise, headache, mild neck stiffness, myalgia and arthralgia often accompany EM.[1][4]

Without treatment, EM resolves spontaneously over a four-week period, on average.

Later (extracutaneous) disease: Approximately 20% of children with LD first present to a health care provider with extracutaneous signs or symptoms that are compatible with LD. These cases may also have a recent past history of EM lesions (single or multiple) and non-specific low-grade fever, myalgia, and fatigue upon questioning further.[4]

Other manifestations (with or without rash) include an isolated facial nerve palsy, arthritis, heart block (or carditis) or meningitis (severe headache, fever), which is usually lymphocytic predominant.[4][9]-[11] The most common late-stage symptoms are pauciarticular arthritis affecting large joints, especially the knees, which may manifest weeks to months (mean four months) after the tick bite. Arthritis can occur without a history of earlier stages of illness. Peripheral neuropathy and central nervous system manifestations can also occur, although rarely in children.[4]

|

Figure 4) Erythema migrans rash showing the classic ‘bull’s eye’ form. Reproduced from reference 1 © All rights reserved. With permission from the Minister of Health, 2014 |

How is the diagnosis of LD made?

Testing should be carried out at an approved provincial, territorial or national public health laboratory in Canada. Test results from private laboratories not approved by Health Canada, provincial or territorial governments cannot be relied upon for accuracy nor validity.

Early, localized (cutaneous) disease: In general, the diagnosis of LD is clinical (see EM, above), supported by a history of potential tick bite in an area where it is known or suspected that black-legged ticks have been established. However, because tick populations are expanding, it is possible that LD can be acquired outside of currently identified areas. Such a possibility should be considered when assessing patients. Patients with EM should be diagnosed and treated without laboratory confirmation,[1][4][10][11] because antibodies against B burgdorferi are often not detectable by serodiagnostic testing within the first four weeks after infection (Table 1).[4][12][13]

Later (extracutaneous) disease: All other clinical manifestations of possible LD should be supported by laboratory confirmation.[13] Two-tiered serological testing, including an ELISA screening test followed by a confirmatory Western blot test, is used to supplement clinical suspicion of extracutaneous LD (Figure 5). Two-tiered testing is necessary because the ELISA may yield false-positive results from antibodies directed against other spirochetes, viral infections or autoimmune diseases.[1] Table 1 provides information related to the performance characteristics of serological assays in different clinical presentations of LD.[6][14]

Supplemental tests can detect Borrelia species that cause LD outside of North America. Therefore, travel history should be documented.[1]

Some individuals treated with antimicrobials for early LD never develop antibodies against B burgdorferi. They are cured.[4][13]

Most individuals with extracutaneous disease have antibodies against B burgdorferi. Once such antibodies develop, they persist for years. A decline in antibody levels is not useful to assess treatment response.[1][3] Serological test results for LD should be interpreted along with careful consideration of the clinical setting and quality of the testing laboratory.[1][15]Tests of joint fluid for antibody to B burgdorferi and urinary antigen detection have no role in diagnosis.[3] In suspected Lyme meningitis, testing for intrathecal immunoglobulin M or immunoglobulin G antibodies may be helpful.[1][5][14]

|

TABLE 2. Antibiotic therapy for children and youth with Lyme disease |

||

|

Drug, route |

Dosage |

Maximum per day |

|

Oral |

||

|

Doxycycline |

4 mg/kg to 4.4 mg/kg per day, in two divided doses |

200 mg |

|

Amoxicillin |

50 mg/kg/day, in three divided doses |

1.5 g |

|

Cefuroxime

Azithromycin (if unable to take doxycycline, amoxicillin or cefuroxime) |

30 mg/kg per day, in two divided doses 10 mg/kg/day |

1 g

500 mg |

|

Intravenous |

||

|

Ceftriaxone |

50 mg/kg to 75 mg/kg once daily |

2 g |

|

Data adapted from references 4 and 10. For patients allergic to penicillin, the alternative drug is cefuroxime. Macrolides (azithromycin, clarithromycin and erythromycin) have lower efficacy. Patients treated with macrolides should be closely observed to ensure resolution of clinical manifestations.[1][10][11] |

||

How is LD treated?

Treatment of LD should follow the clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America[1][10][11] and the American Academy of Pediatrics (Tables 2 and 3).[4]

There has been a shift to using shorter durations of antimicrobials and to more permissive use of oral drugs in select circumstances (Tables 2 and 3). Additionally, data on the safety of short courses of doxycycline for children <8 years old, coupled with its proven efficacy for treating LD, including meningitis, has prompted more permissive use of this antimicrobial.[16]

Arthritis frequency has decreased in the United States, probably because of improved recognition and earlier treatment of patients with early LD. Up to one-third of LD patients with arthritis experience residual synovitis and joint swelling, which almost always resolve without repeating the antibiotic course. For patients who have persistent or recurrent joint swelling after a recommended course of oral antibiotic therapy, some experts recommend retreatment with another four-week course of oral antibiotics or with a course of parenteral ceftriaxone.[10] For cases with ongoing arthritis, consultation with an expert is recommended.[4] Consider hospitalization and constant monitoring for a child with heart block and syncope that may rapidly worsen enough to require a pacemaker.[10]

The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction (fever, headache, myalgia and an aggravated clinical picture lasting <24 h) can occur when therapy is initiated. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents should be started and the antimicrobial agent continued.[4]

Approximately 10% to 20% of cases experience lingering symptoms of fatigue and joint and muscle aching that last longer than six months. The clinical term for this condition is persistent ‘post-treatment lyme disease syndrome’ (PTLDS). The exact cause of this response is not yet known. Most medical experts believe that lingering symptoms are the result of residual damage to tissues and the immune system.[17][18] Long-course antibiotic treatments do not provide long-term improvement in PTLDS cases.[19]

|

Figure 6) How to remove a tick. Reproduced with permission from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, USA) |

How to remove a tick

- Use fine-tipped tweezers to grasp the tick close to the skin surface (Figure 6A).

- Pull upward with steady, even pressure (Figure 6B). Try not to twist or jerk, which can cause the mouthpart of the tick to break off and remain in the skin. If this happens and you are unable to remove the mouthpart easily with clean tweezers, leave it alone and let the skin heal.

- Clean the bite area and your hands with rubbing alcohol, an iodine scrub, or soap and water. [20]

The Public Health Agency of Canada advises people to:

- Keep any ticks they remove themselves in a resealable plastic bag or pill vial and note the location and date of the bite.

- Watch for symptoms and see a health care professional immediately should symptoms appear.

- Take the tick with them to their medical appointment, to verify species and test as needed.[1]

How can LD be prevented?

Physicians should be aware of the epidemiology of tick-borne LD in their area,[1][2][7] and recommend some basic precautions for families living, hiking or camping in rural or wooded areas where they may be exposed to ticks.[1][2][3]

- Where play spaces adjoin wooded areas, landscaping can reduce contact with ticks.[3] A pictogram from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is available at: www.cdc.gov/lyme/prev/in_the_yard.html

- Apply 20% to 30% DEET or icaridin repellents. Repellents can be applied to clothing as well as to exposed skin. Always read and follow label directions.[1][21]

- Do a ‘full body’ check every day for ticks. Promptly remove ticks found on yourself, children and pets. Shower or bathe within two hours of being outdoors to wash off unattached ticks.[1]

For more information on how to prevent tick bites, refer to a recent practice point from the Canadian Paediatric Society at: www.cps.ca/en/documents/position/preventing-mosquito-and-tick-bites.

Postexposure antibiotic therapy

The risk of acquiring Lyme disease from a tick bite, even in a highly endemic area, is low, at approximately 3%. If the tick is engorged, the risk increases to 25%. Therefore, if the tick is flat when removed, risk is lower. Consensus on postexposure prophylaxis for LD is that there may be some benefit when the tick is engorged. Some experts recommend prescribing doxycycline 200 mg (or 4.4 mg/kg) as a single dose for children and youth after a tick bite. Prophylaxis can be started within 72 h of removing a tick, even if it has been attached for ≥36 h. As the risk of infection is extremely low if attachment is <36 hours, prophylaxis is not indicated in this circumstance. [1][4][7][10] Data are insufficient to recommend amoxicillin prophylaxis in younger children.[1][4][10][11]

In Canada, such prophylaxis should be considered in ‘known endemic areas’ (see Table 1 and Figure 1 in reference 1). Physicians should bear in mind that the true prevalence of B burgdorferi is often unknown and that the geographical range of infected ticks is expanding in some areas.[1] The Public Health Agency of Canada continues to monitor the distribution and prevalence of infected ticks as well as cases of LD.[1][7]

A vaccine to prevent LD in humans is not available at the present time.[1][4]

Post Lyme Disease Persistent Symptoms

Non-specific post Lyme disease persistent symptoms (such as fatigue) can occur after adequate treatment of the initial infection. This does not require retreatment with antibiotics as this has not been shown to be beneficial. Furthermore, additional antibiotic therapy will promote colonization with resistant bacteria and can cause harm. Instead, care should be provided to either establish another diagnosis or provide ongoing support. [22]

Selected resource:

Government of Canada. Lyme disease (video): http://healthycanadians.gc.ca/video/lyme-eng.php (Accessed July 22, 2014).

Acknowledgements

This position statement was reviewed by the Acute Care and Community Paediatrics Committees of the CPS. Special thanks are due to Drs Nicholas Ogden and Michel Deilgat, with the Centre for Food-borne, Environmental and Zoonotic Infections Diseases, and Dr L Robbin Lindsay, Research Scientist, Field Studies, for the Public Health Agency of Canada’s Lyme Disease Surveillance Group.

CPS INFECTIOUS DISEASES AND IMMUNIZATION COMMITTEE

Members: Natalie A Bridger MD; Jane C Finlay MD (past member); Susanna Martin MD (Board Representative); Jane C McDonald MD; Heather Onyett MD; Joan L Robinson MD (Chair); Marina I Salvadori MD (past member); Otto G Vanderkooi MD

Liaisons: Upton D Allen MBBS, Canadian Paediatric AIDS Research Group; Michael Brady MD, Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics; Charles PS Hui MD, Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel (CATMAT), Public Health Agency of Canada; Nicole Le Saux MD, Immunization Monitoring Program, ACTive (IMPACT); Dorothy L Moore MD, National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI); Nancy Scott-Thomas MD, College of Family Physicians of Canada; John S Spika MD, Public Health Agency of Canada

Consultant: Noni E MacDonald MD

Principal author: Heather Onyett MD

Updated by: Jane McDonald MD, Nicole Le Saux MD

References

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Lyme disease and other tick-borne diseases: Information for healthcare professionals: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/id-mi/tickinfo-eng.php (Accessed July 14, 2014).

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Lyme Disease: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/id-mi/lyme-fs-eng.php (Accessed July 14, 2014).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme disease: www.cdc.gov/Lyme (Accessed July 17, 2014).

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Lyme disease (Lyme borreliosis, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato infection). In: Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, Long SS, eds. Redbook: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 31st edn. Itasca, IL: AAP, 2018:515-23.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Tickborne diseases of the United States: A reference manual for health care providers (2013): www.cdc.gov/lyme/resources/TickborneDiseases.pdf (Accessed July 14, 2014).

- Sider D, Patel S, Russell C, Jain-Sheehan N, Moore S. Technical report: Update on Lyme disease prevention and control (March 2012). Public Health Ontario: www.publichealthontario.ca/en/eRepository/PHO%20Technical%20Report%20-%20Update%20on%20Lyme%20Disease%20Prevention%20and%20Control%20Final%20030212.pdf (Accessed July 14, 2014).

- Public Health Agency of Canada, Canada Communicable Disease Report. Lyme disease. Vol. 40-5 (March 6, 2014): www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/ccdr-rmtc/14vol40/dr-rm40-05/index-eng.php (Accessed July 14, 2014).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Division of Vector-Borne Diseases. Clinical manifestations of confirmed Lyme disease cases—United States, 2001-2010: www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/chartstables/casesbysymptom.html (Accessed July 14, 2014).

- Cherry J, Demmler-Harrison G, Kaplan S, Steinbach WJ, Hotez P. Lyme disease. In: Feigin and Cherry’s Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, 7th edn. Toronto: Elsevier-Saunders, 2014:1729-39.

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43(9):1089-1134. (Erratum in 2007;45:941): http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/43/9/1089.long (Accessed July 14, 2014).

- Lantos PM, Charini WA, Medoff G, et al. Final report of the Lyme disease review panel of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51(1):1-5.

- Henry B, Crabtree A, Roth D, Blackman D, Morshed M. Lyme disease: Knowledge, beliefs, and practices of physicians in a low-endemic area. Can Fam Physician 2012;58(5):e289-95.

- Halperin JJ, Baker P, Wormser GP. Common misconceptions about Lyme disease. Am J Med 2013;126(3):264.el-7.

- Aguero-Rosenfeld ME, Wang G, Schwartz I, Wormser GP. Diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2005;18(3):484-509.

- Centers for Disease and Prevention. Notice to readers: Caution regarding testing for Lyme disease. MMWR 2005;54(05):125: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5405a6.htm (Accessed July 14, 2014).

- Cross R, Ling C, Day NP, McGready R, Paris DH. Revisiting doxycycline in pregnancy and early childhood – Time to rebuild its reputation? Expert Opin Drug Saf 2016;15(3):367-82.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome: www.cdc.gov/lyme/postLDS/index.html (Accessed July 14, 2014).

- Sood SK Lyme disease in children. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2015;29(2):281-94

- Berende A, ter Hofstede HJM, Vos FJ, et al. Randomized trial of longer-term therapy for symptoms attributed to Lyme disease N Engl J Med 2016;374(13):1209 20.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tick removal: www.cdc.gov/ticks/removing_a_tick.html (Accessed May 6, 2014).

- Canadian Paediatric Society. Preventing mosquito and tick bites: A Canadian update. Paediatr Child Health 2014;19(6):326-8.

- Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. AMMI Canada Position Statement on the Diagnosis and Treatment of People with Persistent Symptoms That Have Been Attribute to Lyme Disease. https://www.ammi.ca/Content/03.17.19%20AMMI%20Canada%20Position%20Statement%20%28EN%29.pdf Accessed June 3, 2020

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this position statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. Internet addresses are current at time of publication.

Last updated: May 27, 2021