Position statement

Preventing and treating infections in children with asplenia or hyposplenia

Posted: Nov 6, 2019

Principal author(s)

Marina I Salvadori, Victoria E Price; Canadian Paediatric Society, Infectious Diseases and Immunization Committee

Revised by Nicole Le Saux, Marc Lebel, Dorothy Moore, Karina Top, Michelle Barton-Forbes, Ari Bitnun, Laura Sauve, Ruth Grimes

Abstract

Children with asplenia or hyposplenia are at risk of developing overwhelming sepsis. Health care providers caring for children with asplenia should ensure the best outcomes by using preventive strategies that focus on parent and patient education, immunization, antibiotic prophylaxis, and aggressive management of suspected infection. This updated position statement replaces a prior document from 2014 because new vaccines have become available and information on epidemiology has evolved.

Keywords: Antibiotic prophylaxis; Immunization; Sepsis; Splenectomy

Children can have absent or defective splenic function as a result of congenital anatomical absence of a spleen, surgical removal of the spleen, or medical conditions that result in poor or absent splenic function. Sickle cell anemia is a common cause of this condition in Canada. Absent or defective splenic function is associated with a high risk of fulminant bacterial sepsis, especially with encapsulated bacteria. Splenectomized children younger than 15 years of age and congenitally asplenic infants are at greater risk of developing overwhelming postsplenectomy sepsis than adults.[1] Individuals with underlying blood disorders, such as hemoglobinopathies (e.g., sickle cell disease, thalassemia major) or hereditary spherocytosis, are at greater risk than those who have undergone a splenectomy because of trauma.[1] Asplenic patients are at risk of overwhelming sepsis throughout their life span, with the highest frequency of sepsis reported in the first three years postsplenectomy or in the first three years of life, if congenitally asplenic.[2] Asplenic patients with sepsis from encapsulated organisms have a 50% to 70% mortality rate, with the highest mortality rate reported in children younger than two years of age.[3][4]

Most fulminant sepsis in asplenic patients is due to bacteria encapsulated by a polysaccharide capsule. Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common organism causing sepsis and is isolated in at least 50% of cases. Other encapsulated bacteria (e.g., Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), Neisseria meningitidis, and Salmonella species are less common than pneumococci.[5] Sepsis associated with cat and dog bites due to Capnocytophaga species carry high morbidity.[6] Other causes of sepsis, such as Escherichia coli or, more recently, Bordetella holmesii infection, have been described.[7] Asplenic patients are also more susceptible to severe or fatal malaria [8] and to infection by the protozoan Babesia.[9]

Health care providers caring for children with asplenia should ensure the best outcomes with preventive strategies: parent and patient education, immunization, antibiotic prophylaxis, and the aggressive management of suspected infection.

Parent and patient education

Although immunization and prophylactic antibiotics are effective, they do not provide complete protection. Children with asplenia and their families must be educated about the risk of sepsis and instructed to seek medical attention promptly when the child is ill or has a fever. Heightened infection risk continues into adulthood. Recognizing postsplenectomy sepsis can be difficult and death may occur in a matter of hours. The importance of using prophylactic antibiotics and vaccines should be emphasized repeatedly.

Vulnerable patients should wear a MedicAlert bracelet. When travelling, they should carry a note from their physician stating their diagnosis, associated risks, and a suggested medical management plan should they become ill. They should be aware of their increased risk of infection after animal bites, especially with Capnocytophaga canimorsus from dog bites, and must be given appropriate antibiotics, such as amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, if they are bitten.

Immunization

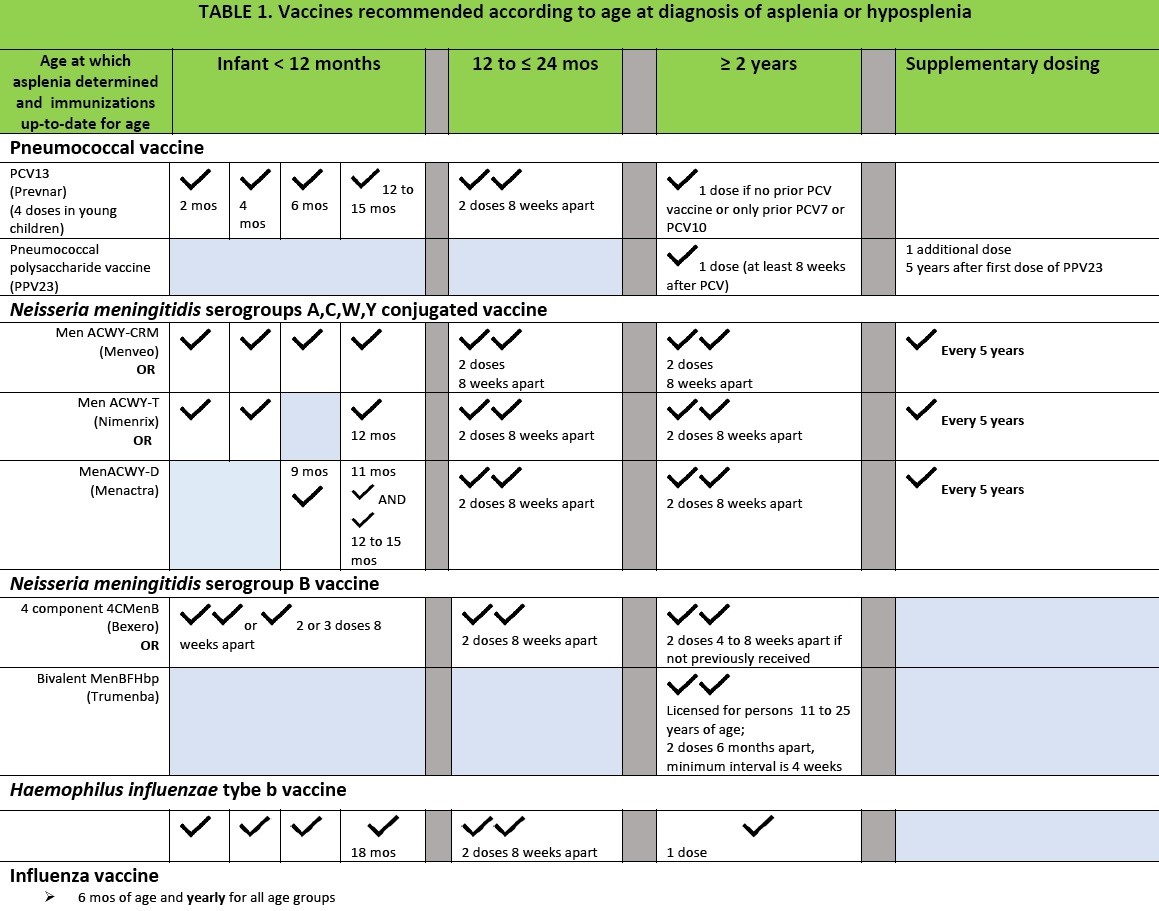

All patients should receive the standard childhood and adolescent immunizations at the recommended age. However, due to the risk of fulminant sepsis from encapsulated bacteria, supplementary immunizations against S pneumoniae, Hib and N meningitidis should be ensured, and may be administered on an earlier schedule than is routine (Table 1).

Pneumococcus

Pneumococcus

All asplenic or hyposplenic patients should receive both the conjugated 13-valent pneumococcal vaccine and the 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine.[10][11]

- The immunization schedule for pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13 (Prevnar-13)) should be a primary series of four doses at two, four, six, and 12 to 15 months of age. Children between 12 and 24 months of age without previous doses of PCV13 should receive two doses at least eight weeks apart. Patients >24 months of age need only one dose of PCV13. Even when children have received all the required doses of PCV7 or PCV10 in the past, they should be given one dose of PCV13 as soon as possible.

- The pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23 (Pneumovax)) should be administered about 8 weeks after receipt of the appropriate number of PCV13 doses for supplemental protection. This interval will ensure ‘priming’ with the conjugated protein vaccine, followed by the broader spectrum, though less immunogenic, polysaccharide vaccine. A booster dose of PPV23 should be given five years after the first dose.

- If asplenic patients have previously received only PPV23, they should receive one dose of PCV13 one year after receiving the PPV23 vaccine.

Meningococcus

All asplenic or hyposplenic patients should receive conjugate quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine (MCV4)) against serogroups A,C,W,and Y as well as vaccine to prevent serogroup B meningococcus as per the schedule that coincides with the age at diagnosis of asplenia or hyposplenia.[12] Vaccines licensed in Canada against the ACWY serogroups include Menveo (GlaxoSmithKline, Canada), which can be administered under license starting at two months of age), Menactra (Sanofi Pasteur, Canada) (licensed starting at nine months of age), and Nimenrix (Pfizer, Canada) (licensed starting at 6 weeks of age).

- Infants should receive MCV4 as a primary series of four doses at two, four, six, and 12 to 15 months of age or on a three-dose schedule (2,4,12 months, if using Nimenrix). Children identified as asplenic or hyposplenic from 12 months to 23 months of age should receive two doses of MCV4, eight weeks apart. Patients identified after two years of age should receive two doses of MCV4, eight weeks apart.

- Vaccinated patients should be revaccinated with MCV4 every five years pending further information on duration of immunity.

- Vaccines licensed in Canada for protection against serogroup B include a four-component vaccine, Bexero (GlaxoSmithKline, Canada), which can be administered under license starting at two months of age), and a bivalent recombinant lipoprotein (rLP2086), Trumenba (Pfizer, Canada) (licensed starting at 10 to 25 years of age).

- Infants and and children should be given 4CMenB (Bexsero). Infants 2 to 11 months of age should receive a two- or three-dose schedule administered 8 weeks apart. Children 12 months to 10 years of age should receive two doses at least 8 weeks apart.

- Children 11 to 18 years of age can be given 4CMenB (Bexsero) or bivalent recombinant vaccine (Trumenba) in a two-dose series, six months apart (with a minimum interval of four weeks).

Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib)

- The recommended vaccination schedule for Hib is a primary series of three doses given at two, four, and six months of age, with a booster dose at 18 months.

- All patients ≥5 years of age who have never received Hib immunization or have missed one or more doses should receive one dose. Some experts recommend one additional dose of Hib vaccine for all asplenic patients older than five years of age, even if they were fully immunized previously.

- Children with asplenia who present with a life-threatening Hib infection should receive Hib vaccine because the infection itself does not confer lifelong protection.

Influenza

- Yearly seasonal influenza vaccine is recommended, starting at six months of age, to lower the risk of secondary bacterial infections.

Other

- All asplenic patients travelling to countries with less stringent food safety and water supply standards than Canada may be at risk for Salmonella infection, and should be immunized for S typhi.[13]

Household contacts

- Household contacts of asplenic patients should receive all age-appropriate vaccines and the yearly influenza vaccine.

Timing of immunizations in elective splenectomy

When a patient is undergoing an elective or semielective splenectomy, there is some evidence that the best responses occur when vaccines are administered at least two weeks before the surgery is performed. When this timing is not possible, it is optimal to begin immunizations at least two weeks postsplenectomy.[14] However, in situations for which vaccines are not administered before splenectomy, the benefit of waiting two weeks postsplenectomy must be carefully weighed against the possibility that the patient may not be vaccinated at all; sometimes the best choice is to vaccinate the child before discharge from hospital.

Antibiotic prophylaxis for children with asplenia or hyposplenia

Immunizations do not fully protect against infections with encapsulated bacteria, making antibiotic prophylaxis a second, vital aspect of care. Table 2 provides dosing information for antibiotic prophylaxis. Because S pneumoniae is the most common cause of severe infections in children with asplenia or hyposplenia, with significant associated mortality, patients younger than five years of age should all receive antibiotic prophylaxis.[4][15]

Controversies exist with respect to duration of antibiotic prophylaxis. Issues include the underlying disease and the effect of prophylaxis on the emergence of penicillin-resistant pneumococci. The single prospective controlled study that showed an 84% reduction in infection was conducted in a population of patients with sickle cell disease; these findings may not apply to all patients with poor splenic function. The age at which antibiotic prophylaxis should be discontinued is the most controversial topic. The 2018 Red Book from the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends prophylaxis until the child is five years of age and a minimum of one year of prophylaxis for children older than five years of age postsplenectomy, provided the child has received all the appropriate pneumococcal vaccinations.[4] The 2011 British Committee for Standards in Haematology and Australian 2017 guidelines recommend that prophylactic antibiotics be continued, especially if: children are younger than 16 years of age; have a history of invasive pneumococcal disease; underwent a splenectomy for a hematological malignancy. They further recommend prophylactic antibiotics for all age groups in the first two years postsplenectomy or when there is an underlying immune function impairment.[15][16]

Because most postsplenectomy sepsis occurs within the first two to three years after surgery, the Canadian Paediatric Society’s Infectious Diseases and Immunization Committee recommends antibiotic prophylaxis for a minimum of two years postsplenectomy and for all children <5 years of age. Furthermore, because fulminant septicemia has been reported in adults up to 65 years postsplenectomy, and invasive infection with penicillin-resistant pneumococci has not emerged as a problem for patients on long-term penicillin prophylaxis, lifelong prophylaxis in all cases is ideally recommended. However, the patient’s or family’s compliance and degree of access to medical care, current pneumococcal resistance rates, and previous episodes of life-threatening sepsis must be considered when making or reviewing this decision.

Children who have had or are believed to have had an anaphylactic-type reaction to penicillin should be referred immediately to an allergist to verify the diagnosis and for challenge or desensitization as warranted.[17] Clarithromycin is a recommended alternative; however, this antibiotic is less successful at preventing invasive disease because of higher rates of pneumococcal resistance.

The optimal duration of antibiotic prophylaxis for children who undergo partial splenectomy or who have functional asplenia or polysplenia is unclear from the literature. Until there are recommendations to the contrary, following the guidelines described for children undergoing total splenectomy appears to be the most prudent course.

Malaria prophylaxis

Asplenic and hyposplenic children must be advised of their increased risk of severe malaria and should always seek travel advice. They should also take malaria prophylaxis as appropriate for their age and the type of malaria found in the area to which they are travelling. Preventive measures should be taken, including sleeping under an insecticide-treated bed net or in air-conditioned accommodations, and using insect repellent. Within the first month of returning from a malaria endemic area, and for up to a year afterward, the patient with fever should inform their health care provider and malaria should be included in the differential diagnosis.[8][18]

Initial treatment of suspected sepsis: A medical emergency

Children with asplenia must be seen by a physician immediately if there is a sudden fever or concern about a non-specific febrile illness, or after an animal bite. Sepsis in individuals with asplenia or hyposplenia is a medical emergency because they can die within several hours of fever onset despite appearing well initially. Unless there is an obvious nonbacterial source, a blood culture should be performed but should not delay the administration of antibiotic therapy. All patients should receive ceftriaxone (100 mg/kg/dose, maximum 2 g/dose). Where intermediate or high penicillin-resistant pneumococci are prevalent, administer both ceftriaxone and vancomycin (60 mg/kg/day in divided doses every 6 h). If the patient is being treated in a clinic or office setting, refer immediately to the nearest emergency department. Clinical deterioration can be rapid even after antibiotic administration. Antibiotics should be modified once blood culture results become available.

If the patient has a serious penicillin or cephalosporin allergy, vancomycin and ciprofloxacin can be used. Antibiotics should be modified once blood culture results become available.

Recommendations

To prevent and treat infections in children with asplenia or hyposplenia, the Canadian Paediatric Society recommends that:

- Physicians educate patients and families about the risks associated with asplenia and hyposplenia.

- Children with asplenia and hyposplenia should receive all routine childhood immunizations, and some routine vaccinations should be administered on an accelerated schedule with extra doses. All children with these conditions, regardless of age, should receive vaccines to protect against S pneumoniae, N meningitidis, Hib, and seasonal influenza.

- Prophylactic antibiotics should be administered until patients are at least 60 months of age, and longer for children who experience an episode of invasive pneumococcal disease. Consideration should be given to lifelong prophylaxis.

- Patients with asplenia or hyposplenia must be considered at high risk of serious bacterial infection (i.e., as presenting with a medical emergency). They should wear a Medic Alert bracelet, be promptly assessed whenever fever occurs and started on antimicrobial therapy immediately unless a nonbacterial source is apparent.

Acknowledgements

The initial position statement was reviewed by the Community Paediatrics Committee of the Canadian Paediatric Society.

CPS INFECTIOUS DISEASES AND IMMUNIZATION COMMITTEE

Members: Robert Bortolussi MD (past Chair); Natalie A Bridger MD; Jane C Finlay MD (past member); Susanna Martin MD (Board Representative); Jane C McDonald MD; Heather Onyett MD; Joan L Robinson MD (Chair); Marina I Salvadori MD (past member); Otto G Vanderkooi MD

Liaisons: Upton D Allen MBBS, Canadian Pediatric AIDS Research Group; Michael Brady MD, Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics; Charles PS Hui MD, Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel (CATMAT), Public Health Agency of Canada; Nicole Le Saux MD, Immunization Monitoring Program, ACTive (IMPACT); Dorothy L Moore MD, National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI); Nancy Scott-Thomas MD, The College of Family Physicians of Canada; John S Spika MD, Public Health Agency of Canada

Consultant: Noni E MacDonald MD

Principal authors: Marina I Salvadori MD, Victoria E Price MBChB MMED

Revised by: Nicole Le Saux MD, Marc Lebel MD, Dorothy Moore MD, Karina Top MD, Michelle Barton-Forbes MD, Ari Bitnun MD, Laura Sauve MD, Ruth Grimes MD

References

- Holdwoth RJ, Irving AD, Cuschieri A. Postsplenectomy sepsis and its mortality rate: Actual versus perceived risks. Br J Surg 1991;78(9):1031-8.

- Price VE, Blanchette VS, Ford-Jones EL. The prevention and management of infections in children with asplenia or hyposplenia. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2007;21(3):697-710, viii-ix.

- Bisharat N, Omari H, Lavi I, Raz R. Risk of infection and death among post-splenectomy patients. J Infect 2001;43(3):182-6.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Immunization in special circumstances In: Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, Long SS, eds. Redbook: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 31st edn. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics:88-90.

- Quinti I, Paganelli R. Asplenia. In: Sullivan KE, Stiehm ER, eds. Stiehm’s Immune Deficiencies. London, U.K.: Elsevier, 2015.

- Lion C, Escande F, Burdin JC. Capnocytophaga canimorsus infections in humans: Review of the literature and cases report. Eur J Epidemiol 1996;12(5):521-33.

- Tartof SY, Gounder P, Weiss D, et al. Bordetella holmesii bacteremia cases in the United States, April 2010-January 2011. Clin Infect Dis 2014;58(2):e39-43.

- Bach O, Baier M, Pullwitt A, et al. Falciparum malaria after splenectomy: A prospective controlled study of 33 previously splenectomized Malawian adults. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2005;99(11):861-7.

- Krause PJ, Gewurz BE, Hill D, et al. Persistent and relapsing babesiosis in immunocompromised patients. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46(3):370-6.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Immunization Guide Part 4: Active Vaccines, Pneumococcal Vaccine: www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-4-active-vaccines/page-16-pneumococcal-vaccine.html (Accessed October 9, 2019).

- Halasa NB, Shankar SM, Talbot TR, et al. Incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease among individuals with sickle cell disease before and after the introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44(11):1428-33.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Immunization Guide Part 4: Active Vaccines, Meningococcal Vaccine: www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-4-active-vaccines/page-13-meningococcal-vaccine.html (Accessed October 9, 2019).

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Immunization Guide Part 4: Active Vaccines, Typhoid Vaccine: www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-4-active-vaccines/page-23-typhoid-vaccine.html (Accessed October 9, 2019).

- Shatz DV, Schinsky MF, Pais LB, Romero-Steiner S, Kirton OC, Carlone GM. Immune responses of splenectomized trauma patients to the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine at 1 versus 7 versus 14 days after splenectomy. J Trauma 1998;44(5):765-6.

- Kanhutu K, Jones P, Cheng AC, Grannell L, Best E, Spelman D. Spleen Australia guidelines for the prevention of sepsis in patients with asplenia and hyposplenism in Australia and New Zealand. Intern Med J 2017;47(8):848-55.

- Davies JM, Lewis MP, Wimperis J, Rafi I, Ladhani S, Bolton-Maggs PH; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Review of guidelines for the prevention and treatment of infection in patients with an abscent or dysfunctional spleen: Prepared on behalf of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology by a working party of the Haemato-Oncology task force. Br J Haematol 2011;155(3):308–17.

- Wong T, Atkinson A, t’Jong G, Rieder M, Chan E, Abrams E; Canadian Paediatric Society, Allergy Section. Beta-lactam allergy in the paediatric population. In press.

- Di Sabatino A, Carsetti R, Corazza GR. Post-splenectomy and hyposplenic states. Lancet 2011;378(9785):86-97.

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this position statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. Internet addresses are current at time of publication.

Last updated: Feb 7, 2024