Position statement

Recognizing and responding to children with suspected exposure to intimate partner violence between caregivers

Posted: Nov 14, 2023

Principal author(s)

Melissa Kimber PhD, MSW, RSW, Jill McTavish PhD, MSW, RSW, Michelle Shouldice M.Ed., MD, FRCPC, Michelle G.K.Ward MD, FAAP, FRCPC, Harriet L. MacMillan CM, MD, MSc, FRCPC;, Child and Youth Maltreatment Section

Paediatrics & Child Health, Volume 29, Issue 3, June 2024, Pages 174–180,

Abstract

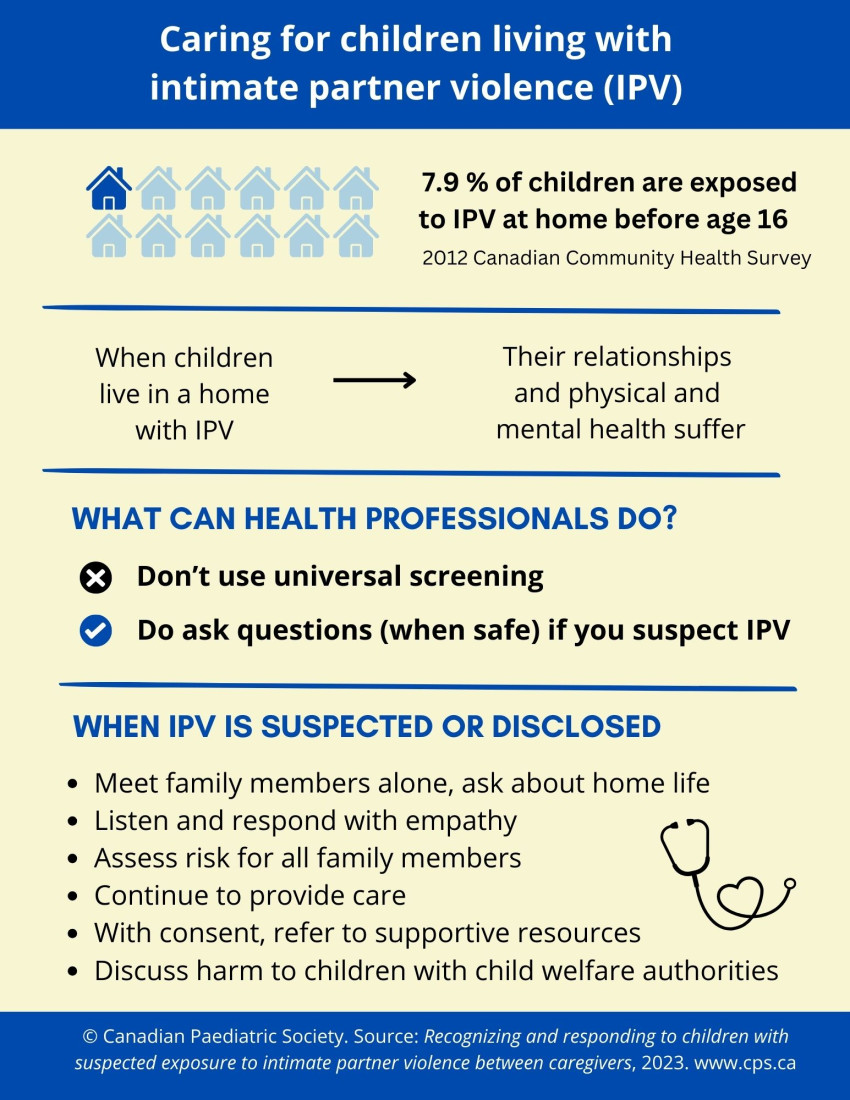

Children’s exposure to intimate partner violence (CEIPV) between parents and other caregivers accounts for nearly half of all cases investigated and substantiated by child welfare authorities in Canada. The emotional, physical, and behavioural impairments associated with CEIPV are similar to the effects of other forms of child maltreatment. The identification of children and youth who have been exposed to intimate partner violence (IPV) can be challenging due to the non-specific behaviours sometimes associated with such exposure, and the stigma and secrecy that often characterize IPV. Also, responding safely to children and youth with suspected CEIPV can be complicated by the need to consider the safety and well-being of a non-offending caregiver. This position statement presents an evidence-informed approach developed by the Violence, Evidence, Guidance, Action (VEGA) Project for the safe recognition and response to children and youth who are suspected of being exposed to IPV.

Keywords: Child exposure to intimate partner violence; Child welfare; Clinical guidance; Intimate partner violence; Trauma- and violence-informed care

Background

Intimate partner violence (IPV) refers to a range of behaviours by a current or former intimate partner that can cause physical, psychological, or sexual harm[1][2]. IPV frequently occurs in the presence of children and youth and can include threats of harm or actual harm toward a child, often as an attempt to control a current or former partner. Childhood exposure to IPV (CEIPV) encompasses violence between adult caregivers or parents (hereafter referred to as “caregivers”) and can have similar negative impacts to childhood physical, sexual, or emotional abuse[3]-[5]. The negative health consequences of CEIPV have contributed to its recognition in Canada as a form of child maltreatment[6]-[8]. CEIPV generally includes any incident of a child or youth witnessing, hearing, being involved in, or being aware of any form of violence involving their caregivers, including physical aggression or assault, sexual assault, harassment or coercion, or psychological abuse, and controlling behaviours.

Paediatricians and other health care professionals have a critical role in helping children and youth who may have been exposed to IPV. This position statement provides an overview of the epidemiology of CEIPV in Canada and presents evidence-informed strategies for recognizing and responding to suspected or disclosed CEIPV from the © Violence, Evidence, Guidance, Action (VEGA) Project’s Family Violence Education Resources[9]. VEGA was developed based on a series of systematic evidence reviews, with input from representatives of 22 national health care and social service organizations, including the Canadian Paediatric Society[9]. For more information about VEGA’s Family Violence Education Resources, see https://vegaproject.mcmaster.ca/.

Prevalence of CEIPV in Canada and associated impairments

Obtaining accurate prevalence data about CEIPV in Canada remains a challenge[10]. The best available data come from the 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey, which asked a representative sample of adults about their CEIPV experiences before age 16[8], including whether they saw or heard any of their caregivers hit each other or another adult in their home. The overall prevalence of CEIPV was 7.9%. A higher proportion of women (8.9%) compared with men (6.9%) reported experiencing CEIPV[8]. To date, no national-level study has assessed CEIPV among children and youth. However, one Quebec sample of 15 secondary schools found that youth (aged 14 to 19) had high rates of CEIPV, with 46.9% of girls and 31.1% of boys reporting they had witnessed verbal or physical IPV between caregivers at least once during their life[11]. The health-related impairments associated with exposure to IPV in childhood or adolescence vary and can depend on several factors (see Table 1 for a general overview)[2][7][8][12]-[23].

Table 1. Impairments associated with children’s exposure to intimate partner violence (CEIPV)

|

Domains of functioning |

Possible impairments |

|

|

|

|

|

IPV Intimate partner violence

Importantly, some children and youth will not experience impairments related to CEIPV. Positive factors that help promote resilience and adaptive well-being include a warm and empathic relationship with a trusted adult, strong caregiver mental health, and emotionally responsive parenting practices[24][25].

VEGA principles for safe recognition of CEIPV in paediatric practice[9]

Skills and knowledge that health care providers can use to safely identify and respond to CEIPV are outlined in VEGA guidance and fit within the CanMEDs framework. Safe recognition and response to CEIPV involves[9]:

- Creating safe environments and interactions

- Being alert to potential signs and symptoms of CEIPV

- Inquiring about CEIPV when signs and symptoms are present

- Taking steps to consider or rule out exposure via phased inquiry

- Responding safely

- Ensuring follow-up care

- Reporting to child welfare services when CEIPV is suspected or disclosed

- Carefully documenting

Creating safe environments and interactions[9]

Evidence indicates that historical and ongoing forms of colonialism and systemic racism are key contributing factors to the disproportionate representation of Black and Indigenous (including First Nations, Métis, and Inuit) children and youth in investigations and reports to child welfare services in Canada[16][26]-[28]. The criticism of harms related to racism and colonialism has leveraged important efforts to raise awareness around inherently racist health care responses, including responses to suspected or disclosed CEIPV. Such efforts include the development, evaluation, and scale-up of trauma- and violence-informed care (TVIC) programs, with the aims of reducing the risk of harm during health care encounters and improving the quality of care for Indigenous and racialized peoples. Three key TVIC principles include: (1) Safeguarding patient collaboration and autonomy in healthcare interactions and decision-making; (2) Exploring experiences of trauma and interpersonal violence in ways that respect the confidentiality and dignity of patients; and (3) Attending to the importance of physical, emotional, and cultural safety during clinical encounters, including self-awareness of one’s own cultural biases and the potential influences of individual and structural racism[9][29]. © VEGA’s “Environment, Approach, and Response” (EAR) model[9], outlined in Table 2, operationalizes TVIC for clinical contexts.

Table 2. The VEGA environment, approach, response (EAR) model for clinic settings

|

VEGA ‘EAR’ model |

Practical strategies for creating safe environments and interactions |

|

Environment (includes institutional, organizational, community, societal factors) |

o Inquiries about IPV with a caregiver should not take place in the presence of a child older than 18 months of age o Children or family members should not be used as interpreters, especially during conversations about potential IPV o A child should be asked about IPV separately from caregivers when developmentally appropriate |

|

Approach (values and principles of TVIC that the provider holds before a health care encounter takes place) |

|

|

Response (safe provider responses in the care encounter) |

|

CEIPV Children’s exposure to intimate partner violence; IPV Intimate partner violence; TVIC Trauma- and violence-informed care

Reference 9

Note: Used with permission from © 2020 VEGA Project, McMaster University. All rights reserved.

Being alert to the potential signs and symptoms of exposure[9]

Two key elements for safely recognizing CEIPV apply to TVIC-informed clinical practice: ongoing assessment of risk factors, signs, and symptoms for IPV exposure; and observing interactions between a child or youth and caregiver(s), and between caregivers[9]. Children or youth with IPV exposure can present with signs and symptoms that overlap with a range of health conditions and other traumatic experiences. Indicators of CEIPV among children or youth can include physical signs and symptoms (e.g., injuries), and significant shifts in behaviours or emotions (e.g., withdrawing from activities that were previously enjoyed or increased oppositional behaviour). Unexplained caregiver behaviours may also signal IPV, such as repeatedly cancelling appointments or deferring to a partner when direct questions are asked. CEIPV risk factors include family financial problems and caregiver unemployment, increasing alcohol and substance use by a caregiver, parental separation, increasingly frequent or intense conflicts or stressful incidents, and caregiver mental health problems or controlling behaviours.

Although each of these risk factors is considered an ‘adverse childhood experience’ (ACE), universal screening for ACEs – which include CEIPV – is not recommended[9]. There is no evidence that universal screening for exposure to IPV leads to health benefits. Moreover, screening without sufficient attention to safety could increase the risk for harm[9][30]-[34]. Clinicians should only inquire about CEIPV when clinically indicated and safe to do so[9]. If the clinician judges that lack of time, skill, or a safe environment precludes inquiry about CEIPV, consider suggesting a referral (e.g., “In hearing what you shared with me today, I think it would be helpful for you to speak with someone with expertise in these matters.”). This approach would be followed by obtaining the patient’s consent to share their information for follow-up care[9]. Consultation with professionals who have specialized knowledge and skills in IPV, including the availability of IPV-specific services, can start with contacting resources at www.sheltersafe.ca or, for Indigenous children or families, www.hopeforwellness.ca.

Inquiring about CEIPV when signs and symptoms are present[9]

Providers need to be alert to the ways CEIPV can overlap with other forms of developmental trauma[35]. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, U.K.) has offered guidance regarding the distinction between ‘considering’ and ‘suspecting’ CEIPV[36]. To ‘consider’ CEIPV is to appreciate it as one of several possible reasons for presenting sign(s) or symptom(s). To ‘suspect’ CEIPV means the provider is reasonably concerned about the risk for exposure because the explanation provided for signs or symptoms is either clinically unreasonable or implausible based on the child’s or youth’s report, their development and stage, or other medical reasons.

Taking steps to consider or rule out exposure via phased inquiry[9]

Clinicians should consider CEIPV whenever signs, symptoms, or risk factors are present. The next step is to meet with each caregiver and child, or youth involved, individually, in a confidential space, if it is developmentally appropriate and safe to do so. After discussing any presenting concerns and outlining the limits of confidentiality, ask first about family relationships[9]. Use open-ended questions for a phased inquiry, such as “How is everyone in your family getting along?” This could be followed by questions about whether a child, youth, or caregiver has any worries: about themselves or anyone in the family (e.g.,“Have you ever felt scared about what might happen to you/your siblings/your parent/your child?”)[9]. Depending on the response, a clinician might ask about specific interactions (e.g.,“What happens in your family when someone gets mad?”)[9].

If a caregiver refuses to meet alone with a clinician or refuses to allow a child or youth to speak alone with a clinician, or a child or youth declines to meet one-on-one, do not ask about CEIPV with other family members present. Instead, try to arrange a follow-up visit to explore signs and symptoms further[9]. When a clinician has concerns about a caregiver’s involvement in or possible perpetration of IPV, they should still be offered the opportunity to be seen individually to provide their impressions of the child(ren) and family. Under no circumstances should information about potential IPV obtained from one caregiver be shared with another caregiver. As soon as a clinician suspects CEIPV or has received a disclosure, no further inquiry regarding CEIPV should occur[9].

Responding safely[9]

Response to suspected or disclosed CEIPV should be warm and supportive (e.g., 'It took you a lot of courage to tell me about this'). Communicate that what has happened is not okay (e.g., “Your mom hitting your mama is not okay”)[9], while avoiding the use of stigmatizing terms (e.g.,‘violent,’ ‘abusive’) unless the patient uses them first[9].

Where possible and especially in cases where a non-offending caregiver has disclosed experiencing IPV, the clinician should assess for safety and for risk of immediate danger[9]. Evaluating safety can begin with asking a caregiver whether they are afraid for their own (or a child’s) safety. Consider asking whether the IPV has become more severe or frequent and whether the individual using violence owns a gun, has ever tried to strangle the non-offending caregiver(s), or has threatened to use a weapon to harm a caregiver, youth, or child. Concerns about safety should be communicated to a child welfare professional and can inform a discussion with the non-offending caregiver as part of resources and safety planning.

An affirmative response to any safety question should initiate discussion of a referral to emergency housing[9][37]. If the non-offending caregiver provides consent for this referral, the clinician can then proceed with making this connection. Clinicians who are concerned about safety should not prevent a child, youth, or caregiver from leaving the practice setting unless they are advised to do so by child welfare authorities, which is a very rare occurrence. Notifying the police is not warranted unless a clinician determines that a child, youth, or non-offending caregiver is at imminent risk of harm, or the caregiver specifically requests that a call be made[2].

Ensuring follow-up care[9]

Ongoing care or referrals provided to children, youth, or non-offending caregiver(s) should be carefully documented, made with their consent, and planned collaboratively with a clinician specializing in IPV and child welfare professionals[9]. Clinicians should be aware of evidence-based interventions for various symptoms and refer as needed. For example, a few studies have suggested that emotion-coaching interventions delivered to mothers of preschool and school-aged children exposed to IPV can improve children’s emotional or behavioural symptoms[25]. For children or youth who exhibit signs or symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, or anxiety, a referral to services offering trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)[9] is warranted. Consider other evidence-based or evidence-informed interventions if trauma-focused CBT is not available, or if the assessment of the child identifies other mental health symptoms or disorders[38]-[40].

Regarding supports for non-offending caregiver(s), consider safety planning, housing options, legal and financial services, and mental health supports. These resources are often available through local shelters for women who have experienced IPV[9]. Various psychological therapies appear to reduce depressive symptoms in caregivers, and may reduce anxiety, but whether they improve other aspects of mental health is still unclear[37][41]. A TVIC approach ensures that clinical interventions and referrals prioritize a family’s cultural values, beliefs, and requests[9]. For example, referring Indigenous families to Indigenous-specific service providers should be explored when requested by the family and wherever possible and appropriate[9][42]. As another example, in rural and remote areas it may not be possible or appropriate to refer a child or their family to a specific service (e.g., legal office) if a member of that family’s community (e.g., extended family) use or are employed at the service, and the family is concerned about privacy. In these instances, obtaining consent to refer the family to a service that is outside the community and able to work with the family remotely may be helpful.

Responding to perpetrators of IPV[9]

There is limited evidence on interventions to assist persons who perpetrate IPV. For individuals with substance use concerns, motivational interviewing and behavioural strategies that support reducing alcohol and substance use may help[2]. Couples therapy is not recommended because risk for harm may increase if relationships involve fear or coercive control[2].

Reporting to child welfare services when CEIPV is suspected or disclosed[9]

In Canada, suspecting CEIPV meets the threshold for a report to child welfare authorities as its own type of maltreatment or as a form of child emotional abuse or neglect[9][43]. Reporting suspected CEIPV to child welfare authorities is a potentially challenging component of the response process and depends on age-related thresholds for each province/territory (see Child Welfare Research Portal for a summary[44]). Reporting can also be complicated by the need to provide for the safety and well-being of children, youth, or non-offending caregivers[9]. When CEIPV is suspected or disclosed, and if it is developmentally appropriate and safe to do so, providers should indicate that they have concerns about safety to the child, youth, or non-offending caregiver(s), and explain their obligation to share this information with the child welfare agency. Clarify that this step is taken with the goal of arranging help for the family[9][45]. Involving child welfare authorities can be stressful both for families and clinicians.

Importantly, it is not within the clinician’s role to determine who is or is not an offending caregiver: that is the role of child welfare authorities[9]. When a suspicion or disclosure of CEIPV arises and it is clear to the clinician from what the child or youth has communicated that the accompanying caregiver is a non-offending caregiver, that caregiver can be given the opportunity to participate in the reporting process[9][45]. Rarely, for reasons of safety, it may not be possible to inform the child, youth, and non-offending caregiver(s) of the need to contact child welfare[9]. Any concerns about the possibility of a child welfare investigation elevating the risk for IPV should be shared by the clinician to the child welfare professional, during the reporting process. Also, if the child, youth, or caregiver is uncomfortable with participating in the reporting process, clinicians can offer to communicate specific statements they would like to be made on their behalf. Clinicians should refrain from speculating or making promises about how the child welfare authority will respond to the report. The clinician’s role is to provide support by listening actively, showing compassion, remaining nonjudgmental, and validating expressed concerns[9]. In cases where the clinician is aware of legal separation or custody proceedings, consider asking the child welfare professional for guidance on reporting and response procedures going forward. Provided the child welfare professional agrees with doing so, clinicians should share any plans for follow-up by the child welfare agency with the child, youth, and non-offending caregiver[9].

Document carefully

Carefully document what is seen and heard during interactions with the child, youth, or caregivers, and with child welfare professionals. Principles for safe and effective documentation include detailed record keeping. For example, note discrepancies in a child’s or youth’s (or caregiver’s) account of behaviour or events. Focus on facts (e.g., “According to patient, partner became angry about mom’s alcohol use”), and verbatim statements made by the child, youth, or caregiver (e.g., Patient reported that on Monday evening “dad threw the TV remote at mom, and it hit her in the face, and she cried”). Note interactions and observations that preceded the CEIPV disclosure, or those which prompted the clinician’s suspicion of CEIPV. Also document the reporting process and involvement by child welfare authorities[9]. Documentation should state who provided the information and the information given. Avoid interpreting, endorsing, or questioning the information provided. Where electronic medical records allow clinicians to ‘flag’ safety concerns, this should be considered, but avoid stigmatizing language as described above[9].

Summary

Child and youth exposure to IPV is both common and challenging. CEIPV is a form of child maltreatment with health effects and consequences that are similar to other forms of maltreatment. VEGA’s evidence-based guidance on safely identifying and responding to CEIPV includes using the principles of TVIC for all children, youth, and families and starts with a phased inquiry when concerns of CEIPV arise. Clinicians can then take a stepwise approach to prioritizing the needs and safety of the child, youth, and non-offending caregiver(s) via respectful responses, assessing risk for immediate danger, providing ongoing care to address the impacts of IPV, and reporting suspected or disclosed CEIPV to child welfare professionals[9]. In line with the evidence and the VEGA Project[9], recommendations for clinicians, regulatory bodies, health professional education programs, and government stakeholders are outlined below.

Recommendations

To assist in the recognition of children and youth who are exposed to intimate partner violence (IPV), clinicians should:

- Use the principles of trauma- and violence-informed care (TVIC) and the © Violence, Evidence, Guidance, Action (VEGA) Project’s Environment, Approach, Response (‘EAR’) model[9] to create a safe clinical environment for discussing children’s exposure to intimate partner violence (CEIPV).

- Make discussions about confidentiality and its limits, and safety, a routine part of clinical practice.

- Do not engage in universal screening for CEIPV. Instead, be alert to signs and symptoms that might indicate CEIPV. If present, use open-ended questions and a phased inquiry about the possibility of CEIPV.

- Inquire about CEIPV separately with the child or youth and their caregiver(s), in a private setting.

When responding to a suspicion or disclosure of CEIPV, clinicians should:

- Be warm, empathetic, and non-judgmental.

- Assess the risk of immediate danger of IPV with the non-offending caregiver(s), or consult with an expert with knowledge, skills, and access to safe spaces (e.g., a local women’s shelter or www.sheltersafe.ca, www.hopeforwellness.ca).

- When it is safe to do so, communicate the obligation to report to child welfare authorities, to the caregiver and, if developmentally appropriate, to the child or youth involved.

- Involve the child or youth and non-offending caregiver(s) in the reporting process, whenever possible. If they are unwilling or uncomfortable participating, offer to communicate specific statements they would like to be made on their behalf.

- When reporting to a child welfare agency, communicate and document concerns (and reasons for them) based on specific patient statements or clinical observations.

- Arrange follow-up care collaboratively with the child or youth, non-offending caregiver(s), and child welfare professionals.

Regulatory bodies, health professional education programs, and government stakeholders should:

- Prioritize raising awareness of and improving response to CEIPV, IPV, and other forms of child maltreatment as core components of the curriculum in health professional education.

- Facilitate provider access to continuing professional development opportunities related to CEIPV, IPV, and other forms of child maltreatment.

- Support intersectoral collaboration among front-line providers, child welfare services, and IPV service organizations.

- Raise awareness about CEIPV as a public health problem with significant individual, family, community, and societal impacts.

- Acknowledge the ongoing role of colonialism and systemic discrimination at all levels when identifying and responding to CEIPV.

Acknowledgements

This position statement was reviewed by the Early Years Task Force and the Adolescent Health, Bioethics, Community Paediatrics, Fetus and Newborn, and the Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities Committees of the Canadian Paediatric Society. The CPS Developmental Paediatrics, Global Child and Youth Health, and Social Paediatrics Section Executives also reviewed this statement.

CANADIAN PAEDIATRIC SOCIETY CHILD AND YOUTH MALTREATMENT SECTION EXECUTIVE (2022)

Executive members: Emma Cory MD (President), Natalie Forbes MD (Member-at-large), Amanda Lord MD (Member-at-large), Clara Low-Décarie MD (AMPEQ), Robyn McLaughlin MD (Vice-President), Kathleen Nolan MD (Secretary-treasurer), Marlène Thibault MD (Member-at-large), Tamara Van Hooren MD (Member-at-large), Michelle Ward MD FAAP FRCPC (Past-President)

Principal authors: Melissa Kimber PhD MSW RSW (Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences, McMaster University), Jill McTavish PhD MSW RSW (Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences, McMaster University), Michelle Shouldice M.Ed. MD FRCPC (Department of Paediatrics, University of Toronto), Michelle G.K. Ward MD FAAP FRCPC, Harriet L. MacMillan CM MD MSc FRCPC (VEGA Project Lead) (Departments of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences, and of Pediatrics, McMaster University; Chedoke Health Chair in Child Psychiatry)

References

- World Health Organization. Health care for women subjected to intimate partner violence or sexual violence: A clinical handbook. Geneva, Switzerland/Luxembourg: WHO; 2014.

- Stewart DE, MacMillan H, Kimber M. Recognizing and responding to intimate partner violence: An update. Can J Psychiatry 2021;66(1):71–106. doi: 10.1177/0706743720939676.

- Bair-Merritt MH, Blackstone M, Feudtner C. Physical health outcomes of childhood exposure to intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Pediatrics 2006;117(2):e278–90. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1473.

- Kitzmann KM, Gaylord NK, Holt AR, Kenny ED. Child witnesses to domestic violence: A meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol 2003;71(2):339–52. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.339.

- Su Y, D’Arcy C, Yuan S, Meng X. How does childhood maltreatment influence ensuing cognitive functioning among people with the exposure of childhood maltreatment? A systematic review of prospective cohort studies. J Affect Disord 2019;252:278–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.026.

- Afifi TO, MacMillan HL, Taillieu T, et al. Relationship between child abuse exposure and reported contact with child protection organizations: Results from the Canadian Community Health Survey. Child Abuse Negl 2015;46:198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.05.001.

- Afifi TO, McTavish J, Turner S, MacMillan HL, Wathen CN. The relationship between child protection contact and mental health outcomes among Canadian adults with a child abuse history. Child Abuse Negl 2018;79:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.01.019.

- Afifi TO, MacMillan HL, Boyle M, Taillieu T, Cheung K, Sareen J. Child abuse and mental disorders in Canada. CMAJ 2014;186(9): E324–32. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.131792.

- Used with permission from © 2020 VEGA Project, McMaster University. Violence, Evidence, Guidance, Action (VEGA) Family Violence Education Resources [Internet]. Hamilton, Ont. McMaster University. 2019: https://vegaproject.mcmaster.ca/ (Accessed Aug 10, 2021).

- Gonzalez A, Afifi TO, Tonmyr L. Completing the picture: A proposed framework for child maltreatment surveillance and research in Canada. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can 2021;41(11):392–97. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.41.11.07.

- Boivin S, Lavoie F, Hébert M, Gagné MH. Past victimizations and dating violence perpetration in adolescence: The mediating role of emotional distress and hostility. J Interpers Violence 2012;27(4):662–84. doi: 10.1177/0886260511423245.

- Evans SE, Davies C, DiLillo D. Exposure to domestic violence: A meta-analysis of child and adolescent outcomes. Aggress Violent Behav 2008;13(2):131–40. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2008.02.005.

- Gardner MJ, Thomas HJ, Erskine HE. The association between five forms of child maltreatment and depressive and anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse Negl 2019;96:104082. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104082.

- Kimber M, McTavish JR, Couturier J, et al. Consequences of child emotional abuse, emotional neglect and exposure to intimate partner violence for eating disorders: A systematic critical review. BMC Psychol 2017;5(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s40359-017-0202-3.

- Artz S, Jackson MA, Rossiter KR, Nijdam-Jones A, Géczy I, Porteous S. A comprehensive review of the literature on the impact of exposure to intimate partner violence for children and youth. Int J Child Youth Fam Stud 2014;5(4):493-587.

- Fallon B, Lefebvre R, Trocmé N, et al. Denouncing the continued overrepresentation of First Nations children in Canadian child welfare: Findings from the First Nations/Canadian incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect. 2019: https://cwrp.ca/publications/denouncing-continued-overrepresentation-first-nations-children-canadian-child-welfare (Accessed May 18, 2023).

- Khoury JE, Tanaka M, Kimber M, et al. Examining the unique contributions of parental and youth maltreatment in association with youth mental health problems. Child Abuse Negl 2022;124:105451. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105451.

- Le MTH, Holton S, Romero L, Fisher J. Polyvictimization among children and adolescents in low- and lower-middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse 2018;19(3):323–42. doi: 10.1177/1524838016659489.

- Kimber M, Adham S, Gill S, McTavish J, MacMillan HL. The association between child exposure to intimate partner violence (IPV) and perpetration of IPV in adulthood—A systematic review. Child Abuse Negl 2018;76:273–86. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.11.007.

- Wood SL, Sommers MS. Consequences of intimate partner violence on child witnesses: A systematic review of the literature. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs 2011;24:223–36.

- Manchikanti Gómez A. Testing the cycle of violence hypothesis: Child abuse and adolescent dating violence as predictors of intimate partner violence in young adulthood. Youth Soc 2011;43:171–92.

- Fallon B, Lefebvre R, Filippelli J, et al. Major findings from the Ontario Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect 2018. Child Abuse Negl 2021;111:104778.

- Fallon B, Van Wert M, Trocmé N, et al. Ontario Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect – 2013 Major Findings. Toronto, Ont.: Child Welfare Research Portal; 2015: https://cwrp.ca/sites/default/files/publications/ois-2013_final_0.pdf (Accessed May 18, 2023).

- Fong VC, Hawes D, Allen JL. A systematic review of risk and protective factors for externalizing problems in children exposed to intimate partner violence. Trauma Violence Abuse 2019;20(2):149–67.

- Fogarty A, Wood CE, Giallo R, Kaufman J, Hansen M. Factors promoting emotional‐behavioural resilience and adjustment in children exposed to intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Aust J Psychol 2019;71(1-2):375–89. doi: 10.1111/ajpy.12242.

- Bonnie N, Facey K. Understanding the over-representation of Black children in Ontario child welfare services – Ontario Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect 2018. Toronto, Ont.: Child Welfare Research Portal, 2022: https://www.oacas.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Black-Children-in-Care-OIS-Report-2022-Final.pdf (Accessed May 18, 2023).

- Holmes C, Hunt S. Indigenous Communities and Family Violence: Changing the Conversation. Prince George, B.C.: National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health; 2017: https://www.nccih.ca/docs/emerging/RPT-FamilyViolence-Holmes-Hunt-EN.pdf (Accessed May 18, 2023).

- Truth and Reconcilation Commission of Canada. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015: https://irsi.ubc.ca/sites/default/files/inline-files/Executive_Summary_English_Web.pdf (Accessed May 18, 2023).

- Sweeney A, Perôt C, Callard F, Adenen V, Mantovani N, Goldsmith L. Out of the silence: Towards grassroots and trauma-informed support for people who have experienced sexual violence and abuse. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2019;28(6):598–602. doi: 10.1017/S2045796019000131.

- Campbell TL. Screening for adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in primary care: A cautionary note. JAMA 2020;323(23):2379-80. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4365.

- McLennan JD, MacMillan HL, Afifi TO, McTavish J, Gonzalez A, Waddell C. Routine ACEs screening is NOT recommended. Paediatr Child Health 2019;24(4):272–73. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxz042.

- Anda R F, Porter LE, Brown DW. Inside the adverse childhood experience score: Strengths, limitations, and misapplications. Am J Prev Med 2020;59(2):293–95.

- World Health Organization. WHO mhGAP Guideline Update: Update of the Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) Guideline for Mental, Neurological and Substance use Disorders. May 2015: hhttps://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/204132/9789241549417_eng.pdf?isAllowed=y&sequence=1" Accessed May 18, 2023).

- Feltner C, Wallace I, Berkman N, et al. Screening for intimate partner violence, elder abuse, and abuse of vulnerable adults: Evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2018;320(16):1688-1701. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13212.

- Keeshin B, Forkey HC, Fouras G, et al. Children exposed to maltreatment: Assessment and the role of psychotropic medication. Pediatrics 2020;145(2):e20193751. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3751.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE U.K). Child Maltreatment: When to Suspect Maltreatment in Under 18s. 2009. Updated October 9, 2017: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg89 (Accessed May 28, 2023).

- MacMillan HL. Kimber M, Stewart DE. Intimate partner violence: Recognizing and responding safely. JAMA 2020;324(12):1201-02. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.11322.

- Yunitri N, Kao CC, Chu H, et al. The effectiveness of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing toward anxiety disorder: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Psychiatr Res 2020;123:102–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.01.005.

- Carletto S, Malandrone F, Berchialla P, et al. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2021;12(1): 1894736. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2021.1894736.

- Bastien RJB, Jongsma HE, Kabadayi M, Billings J. The effectiveness of psychological interventions for post-traumatic stress disorder in children, adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2020;50(10):1598–1612. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720002007.

- Hameed M, O’Doherty L, Gilchrist G, et al. Psychological therapies for women who experience intimate partner violence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;7(7):CD013017. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013017.pub2.

- Sistovaris M, Fallon B, Sansone G. Interventions for the Prevention of Family Violence in Indigenous Populations: Policy Brief. Toronto, Ont.: Policy Bench, Fraser Mustard Institute of Human Development, University of Toronto: https://socialwork.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Policy-Brief-Family-Violence-Jan19-reduced.pdf (Accessed May 18, 2023).

- Tonmyr L, Mathews B, Shields ME, Hovdestad WE, Afifi TO. Does mandatory reporting legislation increase contact with child protection? – A legal doctrinal review and an analytical examination. BMC Public Health 2018;18(1):1021. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5864-0.

- Canadian Child Welfare Research Portal. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): What is the definition of the term ‘child’ in the provinces and territories across Canada?: https://cwrp.ca/frequently-asked-questions-faqs (Accessed May 18, 2023).

- McTavish JR, Kimber M, Devries K, et al. Children’s and caregivers’ perspectives about mandatory reporting of child maltreatment: A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ Open 2019;9(4):e025741. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025741.

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this position statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. Internet addresses are current at time of publication.

Last updated: Aug 20, 2024

Click on the image to open it in larger window