Position statement

Skin-to-skin care (SSC) for term and preterm infants

Posted: Jan 11, 2024

Principal author(s)

Gabriel Altit MD, Danica Hamilton RN, Karel O'Brien MD MSc, Fetus and Newborn Committee

Paediatrics & Child Health, Volume 29, Issue 4, July 2024, Pages 238–245,

Abstract

Skin-to-skin care (SSC) is an important part of parent and infant care during the neonatal period and into infancy. SSC should be initiated immediately after birth and practiced as a standard of care in all settings, as well as in the home. There is strong evidence that SSC has a positive effect on breastfeeding and human milk feeding in both term and preterm infants, as well as on mortality, cardiopulmonary stability, and thermoregulation. SSC reduces pain and infant stress, enhances parent–infant bonding, has neurodevelopmental benefits, and has positive effects on parental mental health. The safety and feasibility of providing SSC has been established in term and preterm infants, and SSC is recommended as best practice for all infants. The benefits of SSC outweigh the risks in most situations, and despite challenges, providers should implement procedures and accommodations to ensure that SSC occurs, while providing a safe and positive experience for the parent, family, infant, and health care team. This statement includes all families, as defined and determined by themselves, and recognizes that health communication, language, and terminology must be individualized to meet specific family needs by the health care team.

Keywords: Breastfeeding; Kangaroo care; Neurodevelopment; Skin-to-skin care.

Introduction

Skin-to-skin care (SSC), also termed 'kangaroo care’ (KC), is an important best practice during the neonatal period and should be a standard of care for all infants in birthing or postpartum, neonatal, paediatric, and community settings, as well as in the home. SSC is an integral part of infant adaptation to post-natal life, supporting parents with initiation of human milk feeding and bonding, and enhancing development and physiological stability[1][2]. SSC can be practiced in both health care and home settings, and should be reinforced following discharge from the hospital with family education and support from the health care team. As a safe, low-cost intervention with multiple proven benefits for infants in low-, middle-, and high-income countries, SSC warrants implementation as a global standard of care[3].

SSC begins immediately after birth regardless of method of delivery (vaginal or caesarean) (Table 1). The infant is placed prone on the birthing parent’s bare abdomen or chest, with no clothing separating them. Unless advanced neonatal resuscitation is required, this contact should continue uninterrupted for at least an hour post-birth[4], which is the time needed for the infant to transition through innate behavioural stages that result in a first feed at the breast[5]-[8]. To ensure optimal extrauterine adaptation and establishment of human milk feeding, SSC should be initiated with the birthing parent as the priority. If a birthing parent is unstable, an alternate person designated by the parent or family can undertake SSC.

After first contact, SSC can continue with the infant placed prone on the parent’s bare chest, now wearing only a diaper. For premature and low-birth weight infants, parents should be supported to provide SSC for as long and as often as they are able and willing to do so[4]. Recent analysis of the evidence has led the World Health Organization (WHO) to recommend initiating SSC in this population as soon as possible after birth, then prolonging contact for at least 8 hours per day or as long as possible (up to 24 hours) per day[4]. Interrupting SSC may occur if the infant or birthing parent becomes unstable or if the parent is too fatigued to hold the newborn safely. In these situations, SSC can be prolonged by the other parent or another designated person.

Kangaroo mother care (KMC) is defined as early, continuous, and prolonged skin-to-skin contact between the birthing parent and their infant, with exclusive human milk feeding, although as terms, SSC, KC, and KMC are used almost interchangeably[1]. KMC originated in Bogotá, Colombia to address resource-limited conditions and high infant mortality[9]. KMC is further defined as early, continuous SSC/KC for preterm or low birth weight infants by their birthing parent for prolonged periods of time, up to 24 hours per day, with exclusive human milk feeding, early discharge, and continuation at home[9]. The health care team plays a key supportive role by providing culturally adapted information about SSC, along with equipment and resources to meet family-specific needs. They are responsible for describing the importance of SSC – and facilitating its practice – for all infants, regardless of feeding modality[10] and the infant’s care needs[11] (Table 2).

Importance and benefits of SSC

Breastfeeding and human milk feeding

Strong evidence from randomized control trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews supports SSC’s positive effects on almost all human milk feeding outcomes in term and preterm infants. Studies that included late preterm infants have associated SSC with improved exclusive breastfeeding rates at hospital discharge to 1 month of age, and with any level breastfeeding at 1 to 4 months of age[5]. In systematic reviews and one meta-analysis, SSC in a neonatal setting (including in preterm infants) was found to significantly increase rates of exclusive breastfeeding at discharge and at 1-, 3-, and 4-month follow-ups[1]-[3][12]. There is evidence of a dose-response effect for SSC on human milk feeding in preterm infants, especially when practiced for longer periods per day throughout the hospital stay[13]. SSC, even for short periods of up to 1 hour per session, has been shown to increase the duration of any breastfeeding[1][2]. Furthermore, SSC has been associated with higher volumes of expressed human milk and has an important role as infants transition from tube feeding to feeding at the breast[2].

Mortality

One systematic review demonstrated that infants receiving SSC had consistently lower mortality rates across varied infant populations born in countries with different economic profiles[3]. Another systematic review of primarily low- and middle-income countries found reduced mortality for stabilized preterm infants receiving SSC[12]. A recent large RCT showed that initiating continuous KMC immediately after birth for infants whose birth weight was between 1.0 and 1.799 kg improved neonatal survival by 25%, compared with KMC initiated after stabilization[14]. All three studies also reported lower observed rates of hypothermia and suspected sepsis, which may at least in part explain the lower mortality among these infants[3][12][14].

Cardiopulmonary stability

Studies have investigated the effects of SSC on infant physiology and adaptation. In two studies, infants who received SSC had higher SCRIP (stability of the cardiorespiratory system) scores overall[5]. One recent systematic review of the literature focused solely on the effects of early SSC on infant physiological stability (specifically thermoregulation and stabilization) after birth. SSC started immediately post-delivery was associated with stabilizing physiological parameters, including temperature, oxygenation, and heart rate[15]. The safety and feasibility of providing in-hospital SSC has been established in moderately (32-34 weeks) and extremely (<28 weeks) preterm infants and has been recommended as a standard practice in high and low technology units[16]. Another systematic review suggested that SSC may protect against apnea of prematurity in preterm infants[17].

Infection prevention, enhanced immunity, and microbiome effects

Multiple factors have been shown to influence the microbial colonization of preterm infants, including the use of antibiotics, consumption of human milk, and mode of delivery[18]. The role of SSC in modifying the gut microbiota and their effects on infant risk for sepsis and on brain development is not well understood. But it is known that preterm infants who receive SSC are colonized with their mothers’ bacteria, which help regulate the infant microbiome and decrease colonization by pathologic bacteria post-birth[19]-[21]. Local infection prevention and control (IPAC) guidelines should be followed to prevent nosocomial and horizontal transmission of infections to infants.

Pain management

Multiple reviews have confirmed the efficacy of SSC for alleviating procedural pain in both term[22][23] and preterm[22] infants, especially when combined with breastfeeding. As one example, SSC for at least 10 minutes before receiving an intramuscular injection was shown to reduce pain response in term infants[23].

Stress regulation

Research in developmental psychology and infant mental health has confirmed the essential regulatory function of the birthing parent’s presence for infants and the importance of parental touch. In the literature, leading indicators of stress include infant heart rate variability, infant and maternal cortisol and oxytocin levels, and questionnaires that measure maternal stress[24]. The evidence that SSC can regulate infant stress is mixed. SSC procedures varied among studies, and many used small sample sizes and different inclusion/exclusion criteria or control conditions[25]. However, one recent review of the evidence suggested that SSC improves infant heart rate variability, reduces cortisol, and increases oxytocin levels, effects that support SSC as a stress-reducing intervention and an essential component of quality hospital care[26].

Neurodevelopmental benefits

Infants born preterm are at increased risk for neurodevelopmental differences, which can manifest in many ways[27], including modified hypothalamic adrenal axis (HPA) function[28]. Studies have suggested that in the hospital environment, an infant’s exposure to necessary but stressful medical interventions, separation from parents, and painful procedures, all contribute to impaired maturation of the preterm brain[29][30]. However, research using animal models has suggested that providing birthing parents with care and support during painful procedures can also help mitigate negative hospital-related effects on their infant’s developing brain, in part by increasing secretion of oxytocin, a neuropeptide that enhances the buffering effects of social support on stress response. Moreover, studies have shown that infants who receive SSC have more mature sleep organization, better sleep cycling, and more typical amplitude-integrated electroencephalography (aEEG) development[31].

A recent RCT from China[32] has further confirmed the impact of SSC on infant developmental outcomes. In this study, infants in the control group who had no interaction with parents (which was standard care for that neonatal unit) were compared with infants in the intervention arm, who received SSC for at least 1 hour per day for 14 days. The infants who received SSC showed improved aEEG and neurobehavioural findings on days 7 and 14, and better results on their behavioural and neurological assessments at 3 and 6 months of age compared with the control group. SSC has also been shown to improve infant growth generally[33] and rates of breast/human milk feeding, effects which positively impact the developing infant brain. There is emerging evidence that early visual and vocal contact with parents, facilitated during SSC, promotes the development of infant attachment, attunement, and even language as first steps in development and relational health[34]-[36].

For an infant exposed to substances in utero and at risk for (or experiencing) neonatal abstinence syndrome (or neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome), the contact that SSC provides is a primary non-pharmacological intervention in symptom management[37]-[39]. Regular SSC encourages parental responsiveness and attachment for all infants[40]. SSC promotes improved sleep patterns and has been associated with decreasing both the need for pharmacological treatment in newborns and length of stay in hospital.

Parent–infant interaction and effects on parent mental health

Providing SSC gives parents the opportunity for positive interaction with their infants, even when they require intensive care. Oxytocin release occurs in response to SSC with birthing and supportive parents, and has been shown to reduce stress and anxiety scores[41]. Oxytocin release also promotes bonding and parent–infant attunement. Attunement leads to parents feeling more confident and comfortable taking care of their infant[42]. Systematic reviews have confirmed that SSC has a small protective effect on depression scores in mothers of preterm or LBW infants[43][44]. One review of non-birthing parent interventions in the NICU – mainly SSC and other tactile contacts – demonstrated general positive effects, including on the mental health of non-birthing parents[45]. SSC is a proven best practice that supports infant development and relational health between infants and parents.

Safe SSC in monitored and unmonitored settings

Cases of sudden, unexpected infant collapse associated with SSC in unmonitored settings have been reported, though very rarely (estimated incidence is 2.6 to 133 cases per 100,000 infants), with parental inattention (e.g., through sleep deprivation or exhaustion) being a possible risk factor[46][47]. Most deaths are caused directly by entrapment, suffocation or falls[48]. However, a report based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found implementation of SSC and breastfeeding to be temporally associated with decreasing risk for sudden unexpected infant death in the first 6 days post-birth[49]. With appropriate parental support and guidance, SSC should be part of routine post-natal care, even in post-operative settings.

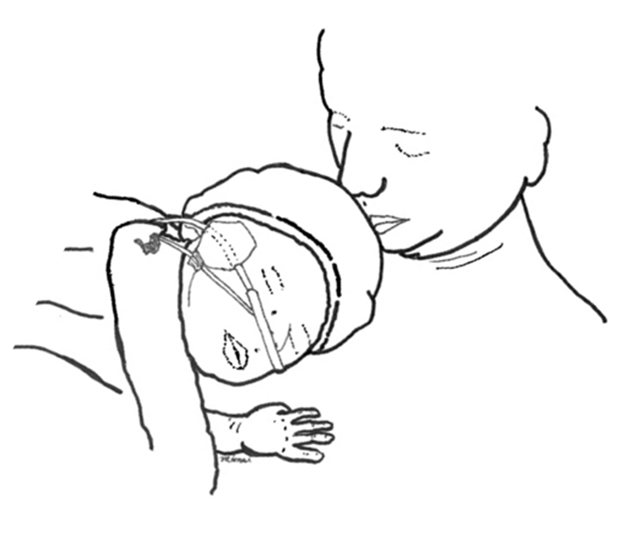

The parent–infant dyad should be observed continuously in the immediate post-delivery setting by a member of the health care team, then regularly during post-partum care[48]. Parents should be taught to attend to their infant’s breathing, activity, colour, tone and positioning, making sure there are no signs of airway obstruction[48]. Proper positioning during SSC allows the infant’s face to be seen, with neck straight or slightly extended (i.e., the ‘sniffing position’) and head turned to the side to avoid airway compromise or covering of the mouth. Health care professionals should assess parents for drowsiness and exhaustion due to the birth experience and provide adequate support for safe SSC. When a parent needs to rest, the infant should be placed skin to skin with the other parent (or an alternate person who is awake and alert) or, if unavailable, in a bassinet, in accordance all with safe-sleep practices[48]-[52].

|

Table 1. Skin-to-skin care immediately following vaginal or cesarean birth |

|

|

Table 2. Ongoing skin-to-skin care, with support |

|

Medications (prescribed or non-prescribed), substance use, and opioid agonist treatment can cause parental drowsiness or withdrawal. Such effects must be addressed to safely support SSC[53]. Additional counselling to ensure safe SSC may be required, and discussions with the parents or family members should be candid about risks while remaining sensitive, respectful, and non-judgmental. Avoid stigmatizing language and put the person first (e.g., “the parent who is using alcohol”). Such discussions are confidential and should only be shared with explicit permission from the birthing parent[53][54].

Studies in preterm infants (including extremely preterm infants) have not shown clinically significant alterations in vital signs or oxygen requirements before and after SSC[55]-[59], though SSC appears to favour a more mature thermoregulation, a slight increase in temperature, and an improvement in some physiological variables[59]-[61]. SSC did not increase the frequency or duration of apneic episodes[62][63] or oxygen consumption[64]. Most studies were based on 60- to 90-minute sessions of SSC.

Various reports have confirmed the feasibility of SSC in premature and term infants who are intubated[55][57][58][65][66] or on non-invasive ventilatory support[58]. There is no evidence of risk for unplanned extubation or dislodgement of lines during SSC[55][66][67]. For added safety, some advocate for the presence of two health care workers to assist with transfer and positioning of equipment (e.g., ventilator tubing)[66]. SSC was also evaluated in 25 neonates receiving intensive care for congenital heart defects[68][69]. During 60 1-hour sessions of SSC, no adverse events (including dislodgement) were identified, despite the presence of multiple lines, tubes, wires, and catheters. Centres have described routinely and successfully providing SSC to infants with chest tubes and ventilators, including high-frequency oscillatory[70] or jet[71] ventilation, demonstrating the feasibility of SSC for critically ill infants. In extremely preterm infants, delaying SSC for the first 72 hours of life may be warranted due to concerns regarding handling and neuroprotection. However, the feasibility of providing SSC opportunities in the same period for this population has also been described without an increase in intraventricular hemorrhage[72]. In monitored settings, an interprofessional team approach is needed to determine whether individual infants are ready for SSC.

Relative contraindications

Relative contraindications to SSC include the presence of an abdominal wall or neural tube defect, postoperative instability (or stability not yet determined), and significant instability associated with clinical handling or prolonged recovery[70]. During therapeutic hypothermia, parental holding should still be considered[73][74]. In almost all medically complex situations, the benefits of SSC outweigh risks. Despite challenges, providers should have procedures and accommodations in place to ensure that SSC occurs, while providing a safe, positive experience for infants, parents, and the health care team.

Procedures and equipment

SSC should not be regarded as optional within hospitals, but rather as part of the essential care provided to infants, even in high-acuity settings. As SSC is increasingly implemented, leading practitioners will need to ensure that supportive and trained personnel, equipment (e.g., bed or armchairs for optimal comfort, screens for privacy), time, and space are provided[75]. Site-specific policies and procedures should be developed by a multidisciplinary group, including families with lived experience, and adapted to local patient populations (e.g., high-acuity unit, nursery, hospital ward). The aim is to promote early and maximal SSC opportunities for infants and families, while ensuring that parents and the health care team have appropriate resources. Some published guidelines, such as those referenced here for post C-section care[69][76], can be adapted for local conditions.

Consider training courses, simulation use, and practice drills involving care providers and parents in neonatal units and other nursery settings, with focus on the transfer of infants on respiratory or other supports to and from a parent’s chest. Most responders to an online survey[77] targeting neonatal health care providers agreed that an SSC-assistive device (e.g., a wrap, fabric, or garment to aid proper positioning during SSC) that still allows for rapid access to the infant by care providers, would help a parent rest while the infant is on a monitor, and potentially improve the parental experience of SSC. However, the lack of such devices should never be a barrier to providing SSC. Finally, trained personnel should be available in higher acuity settings to help transfer infants on supportive technologies and monitor SSC sessions. When SSC is fully implemented in Canada as a best practice and standard of care, it will provide a safe, positive, and beneficial life experience for infants and parents alike.

Recommendations

To establish skin-to-skin care (SSC) as proven best practice for all infants, in all neonatal and home settings, the following recommendations are made.

- Paediatricians and perinatal care providers should counsel and promote SSC with expectant parents, focusing on benefits for breastfeeding, improved immunity, and enhancing development, physiological stability during transition, and early bonding.

- Hospitals, birthing centres, and nursery care settings should:

- Engage families with lived experience in developing SSC policies and procedures, and ensure that informed parental decisions are reflected in birth planning.

- Adapt SSC guidelines to meet local conditions and requirements.

- Train staff to safely transfer and position infants for SSC, including those on ventilatory or other supportive technologies.

- Implement procedures and accommodations to ensure that SSC:

- Begins immediately post-birth and continues uninterrupted for at least 1 hour, until the first breastfeed is completed and routine medications administered, except when resuscitation or other acute care is required.

- Is integrated during medical procedures to help manage infant pain and stress.

- Continues in post-operative and acute care settings.

- Is recorded and reported on daily rounds as a key performance indicator or quality improvement marker.

In addition to the above, neonatal health care teams should:

- Encourage and support parents to provide SSC for as long and as often as they are able and willing to do so, even if their infant is born prematurely or with low birth weight.

- Explain and reinforce the linkage between SSC and human milk supply and breastfeeding, and the importance of both for infant–parent bonding and health.

- Coordinate the transfer of infants to and from a parent with other health care team members when appropriate (e.g., have a respiratory therapist present if an infant is on assisted ventilation).

- Prioritize the birthing parent, but know who, when, and how to engage another parent or alternate caregiver in SSC.

- Provide culturally adapted, family-centred information about SSC, with equipment and resources to meet family-specific needs (e.g., for education, comfort, privacy).

- Monitor for parental fatigue, and counsel against substance use and unsafe sleep arrangements, while remaining sensitive, respectful, and non-judgmental.

- Use an interprofessional approach (in monitored settings) to determine whether acute cases are ready for SSC.

- Document SSC in the infant’s health record.

- At discharge from hospital, reinforce the benefits and routines of SSC with family education and support.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the work of Pamela Hamilton, who constructed the images, and Laura N. Haiek, MD, MSc, for her review and editing. This statement was reviewed by the Acute Care, Community Paediatrics, First Nations, Inuit and Métis Health, Infectious Diseases and Immunization, and Nutrition and Gastroenterology Committees of the Canadian Paediatric Society. It was also reviewed by the CPS Developmental Paediatrics, Global Child & Youth Health, Hospital Paediatrics, and Paediatric Emergency Medicine Section Executives, and by the CPS Early Years Task Force. The statement was further reviewed by members of the Canadian Association of Perinatal and Women's Health Nurses, Clinical Practice Committee, and reviewed and endorsed by the Canadian Association of Neonatal Nurses.

CANADIAN PAEDIATRIC SOCIETY FETUS AND NEWBORN COMMITTEE (July 2022)

Members: Gabriel Altit MD, Anne-Sophie Gervais MD (Resident Member), Heidi Budden MD (Board Representative), Leonora Hendson MD (past member), Souvik Mitra MD, Michael R. Narvey MD (Chair), Eugene Ng MD, Nicole Radziminski MD

Liaisons: Eric Eichenwald MD (Committee on Fetus and Newborn, American Academy of Pediatrics), William Ehman MD (College of Family Physicians of Canada), Danica Hamilton RN (Canadian Association of Neonatal Nurses), Emer Finan MBBCH (CPS Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine Section Executive), Chantal Nelson PhD (Public Health Agency of Canada), R. Douglas Wilson MD (The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada)

Authors: Gabriel Altit MD, Danica Hamilton RN, Karel O'Brien MD MSc

References

- World Health Organization. Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breastfeeding: The Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative for Small, Sick and Preterm Newborns. 2020. (Accessed July 19, 2023).

- World Health Organization. Implementation Guidance: Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breastfeeding in Facilities Providing Maternity and Newborn Services; The Revised Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative. 2018. (Accessed July 19, 2023).

- Boundy EO, Dastjerdi R, Spiegelman D, et al. Kangaroo Mother Care and neonatal outcomes: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2016;137(1):e20152238. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2238.

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations for Care of the Preterm or Low-birth-weight Infant. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2022. (Accessed July 19, 2023).

- Moore ER, Bergman N, Anderson GC, Medley N. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;11(11):CD003519. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003519.pub4.

- Brimdyr K, Cadwell K, Svensson K, Takahashi Y, Nissen E, Widström AM. The nine stages of skin-to-skin: Practical guidelines and insights from four countries. Matern Child Nutr 2020;16(4):e13042. doi: 10.1111/mcn.13042.

- Widström AM, Brimdyr K, Svensson K, Cadwell K, Nissen E. Skin-to-skin contact the first hour after birth, underlying implications and clinical practice. Acta Paediatr 2019;108(7):1192-1204. doi: 10.1111/apa.14754.

- Widström AM, Brimdyr K, Svensson K, Cadwell K, Nissen E. A plausible pathway of imprinted behaviors: Skin-to-skin actions of the newborn immediately after birth follow the order of fetal development and intrauterine training of movements. Med Hypotheses 2020;134:109432. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2019.109432.

- Hubbard JM, Gattman KR. Parent-infant skin-to-skin contact following birth: History, benefits, and challenges. Neonatal Netw 2017;36(2):89-97. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.36.2.89.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Chapter 6: Breastfeeding. Family-centred maternity and newborn care: National guidelines. 2019. (Accessed July 19, 2023).

- Tomlinson C, Haiek LN; CPS Nutrition and Gastroenterology Committee. Breastfeeding and human milk in the NICU: From birth to discharge.

- Conde-Agudelo A, Díaz-Rossello JL. Kangaroo mother care to reduce morbidity and mortality in low birthweight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;2016(8):CD002771. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002771.pub4.

- Oras P, Thernström Blomqvist Y, Hedberg Nyqvist K, et al. Skin-to-skin contact is associated with earlier breastfeeding attainment in preterm infants. Acta Paediatr 2016;105(7):783-89. doi: 10.1111/apa.13431.

- WHO Immediate KMC Study Group; Arya S, Naburi H, et al. Immediate “Kangaroo Mother Care” and survival of infants with low birth weight. N Engl J Med 2021;384(21): 2028-38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2026486.

- Gupta N, Deierl A, Hills E, Banerjee J. Systematic review confirmed the benefits of early skin-to-skin contact but highlighted lack of studies on very and extremely preterm infants. Acta Paediatr 2021;110(8):2310-15. doi: 10.1111/apa.15913.

- Nyqvist KH, Expert Group of the International Network on Kangaroo Mother Care, Anderson GC, et al. State of the art and recommendations. Kangaroo mother care: Application in a high-tech environment. Breastfeed Rev 2010;99(6):812-29. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01794.x.

- Montealegre-Pomar A, Bohorquez A, Charpak N. Systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that Kangaroo position protects against apnoea of prematurity. Acta Paediatr 2020;109(7): 310-16. doi: 10.1111/apa.15161.

- Aguilar-Lopez M, Dinsmoor AM, Ho TTB, Donovan SM. A systematic review of the factors influencing microbial colonization of the preterm infant gut. Gut Microbes 2021;13(1):1-33. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1884514.

- Hendricks-Muñoz KD, Xu J, Parikh HI, et al. Skin-to-skin care and the development of the preterm infant oral microbiome. Am J Perinatol 2015;32(13):1205-16. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1552941.

- Abouelfettoh A, Ludington-Hoe SM, Burant CJ, Visscher MO. Effect of skin-to-skin contact on preterm infant skin barrier function and hospital-acquired infection. J Clin Med Res 2011;3(1):36-46. doi: 10.4021/jocmr479w.

- Stewart CJ, Marrs ECL, Nelson A, et al. Development of the preterm gut microbiome in twins at risk of necrotising enterocolitis and sepsis. PLoS One 2013;8(8):e73465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073465.

- Johnston C, Campbell-Yeo M, Disher T, et al. Skin-to-skin care for procedural pain in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;2(2):CD008435. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008435.pub3.

- Disher T, Benoit B, Johnston C, Campbell-Yeo M. Skin-to-skin contact for procedural pain in neonates: Acceptability of novel systematic review synthesis methods and GRADEing of the evidence. J Adv Nurs 2017;73(2):504-19. doi: 10.1111/jan.13182.

- Ionio C, Ciuffo G, Landoni M. Parent-infant skin-to-skin contact and stress regulation: A systematic review of the literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18(9):4695. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18094695.

- Cañadas CD, Bonillo Perales A, Galera Martínez R, Casado-Belmonte MDP, Parrón Carreño T. Effects of kangaroo mother care in the NICU on the physiological stress parameters of premature infants: A meta-analysis of RCTs. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19(1):583. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19010583.

- Pados BF, Hess F. Systematic review of the effects of skin-to-skin care on short-term physiologic stress outcomes in preterm infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. Adv Neonatal Care 2020;20(1):48-58. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000596.

- Adams-Chapman I, Heyne RJ, DeMauro SB, et al. Neurodevelopmental impairment among extremely preterm infants in the Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics 2018;141(5):e20173091. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3091.

- Brummelte S, Grunau RE, Zaidman-Zait A, Weinberg J, Nordstokke D, Cepeda IL. Cortisol levels in relation to maternal interaction and child internalizing behavior in preterm and full-term children at 18 months corrected age. Dev Psychobiol 2011;53(2):184-95. doi: 10.1002/dev.20511.

- Kommers D, Oei G, Chen W, Feijs L, Bambang Oetomo S. Suboptimal bonding impairs hormonal, epigenetic and neuronal development in preterm infants, but these impairments can be reversed. Acta Paediatr 2016;105(7):738-51. doi: 10.1111/apa.13254.

- Vinall J, Grunau RE. Impact of repeated procedural pain-related stress in infants born very preterm. Pediatr Res 2014;75(5):584-87. doi: 10.1038/pr.2014.16.

- Ludington-Hoe SM, Johnson MW, Morgan K, et al. Neurophysiologic assessment of neonatal sleep organization: Preliminary results of a randomized, controlled trial of skin contact with preterm infants. Pediatrics 2006;117(5):e909-23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1422.

- Wang Y, Zhao T, Zhang Y, Li S, Cong X. Positive effects of kangaroo mother care on long-term breastfeeding rates, growth, and neurodevelopment in preterm infants. Breastfeed Med 2021;16(4):282-91. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2020.0358.

- Charpak N, Montealegre-Pomar A, Bohorquez A. Systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that the duration of kangaroo mother care has a direct impact on neonatal growth. Acta Paediatr 2021;110(1):45-59. doi: 10.1111/apa.15489.

- Filippa M, Lordier L, De Almeida JS, et al. Early vocal contact and music in the NICU: New insights into preventive interventions. Pediatr Res 2020;87(2):249-64. doi: 10.1038/s41390-019-0490-9.

- Buil A, Sankey C, Caeymaex L, Apter G, Gratier M, Devouche E. Fostering mother-very preterm infant communication during skin-to-skin contact through a modified positioning. Early Hum Dev 2020;141:104939. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2019.104939.

- Williams RC; CPS Early Years Task Group. From ACEs to early relational health: Implications for clinical practice.

- Bystrova K, Ivanova V, Edhborg M, et al. Early contact versus separation: Effects on mother-infant interaction one year later. Birth 2009;36(2):97-109. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2009.00307.x.

- Feldman R, Rosenthal Z, Eidelman AI. Maternal-preterm skin-to-skin contact enhances child physiologic organization and cognitive control across the first 10 years of life. Biol Psychiatry 2014;75(1):56-64. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.012.

- Scatliffe N, Casavant S, Vittner D, Cong X. Oxytocin and early parent-infant interactions: A systematic review. Int J Nurs Sci 2019;6(4):445-53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2019.09.009.

- New South Wales Government. NSW Health. Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Substance Use During Pregnancy, Birth and the Postnatal Period. Sydney, Australia: NSW Health, 2014. (Accessed July 19, 2023).

- Cong S, Wang R, Fan X, et al. Skin-to-skin contact to improve premature mothers' anxiety and stress state: A meta-analysis. Matern Child Nutr 2021;17(4):e13245. doi: 10.1111/mcn.13245.

- Wiberg B, Humble K, de Château P. Long-term effect on mother-infant behaviour of extra contact during the first hour post partum. V. Follow-up at three years. Scand J Soc Med 1989;17(2):181-91. doi: 10.1177/140349488901700209.

- Kirca N, Adibelli D. Effects of mother-infant skin-to-skin contact on postpartum depression: A systematic review. Perspect Psychiatr Care 2021;57(4):2014-23. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12727.

- Scime NV, Gavarkovs AG, Chaput KH. The effect of skin-to-skin care on postpartum depression among mothers of preterm or low birthweight infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2019;253: 376-84. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.101.

- Filippa M, Saliba S, Esseily R, Gratier M, Grandjean D, Kuhn P. Systematic review shows the benefits of involving the fathers of preterm infants in early interventions in neonatal intensive care units. Acta Paediatr 2021;110(9):2509-20. doi: 10.1111/apa.15961.

- Bass JL, Gartley T, Lyczkowski DA, Kleinman R. Trends in the incidence of sudden unexpected infant death in the newborn: 1995-2014. J Pediatr 2018;196:104-08. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.12.045.

- Rodriguez NA, Hageman JR, Pellerite M. Maternal distraction from smartphone use: A potential risk factor for sudden unexpected postnatal collapse of the newborn. J Pediatr 2018;200:298-99. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.04.031.

- Feldman-Winter L, Goldsmith JP; AAP Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Safe sleep and skin-to-skin care in the neonatal period for healthy term newborns. Pediatrics 2016;138(3):e20161889. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1889.

- Public Health Agency of Canada, Health Canada, Canadian Paediatric Society, Canadian Institute of Child Health, Canadian Foundation for the Study of Infant Deaths. Joint Statement on Safe Sleep: Preventing Sudden Infant Deaths in Canada. (Accessed August 1, 2023).

- Bartick M, Boisvert ME, Philipp BL, Feldman-Winter L. Trends in breastfeeding interventions, skin-to-skin care, and sudden infant death in the first 6 days after birth. J Pediatr 2020;218: 11-15. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.09.069.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Canadian Paediatric Society, American Heart Association. Textbook of Neonatal Resuscitation, 8th edn. Itasca, IL: APA; 2021.

- Boulton JE, Coughlin K, O’Flaherty D, Solimano A, eds. ACoRN: Acute Care of at-Risk Newborns, 2nd edn. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2021.

- B.C. Women’s Hospital/Health Centre, Provincial Health Services Authority. Rooming‐in Guideline for Perinatal Women Using Substances. 2020:1-49. (Accessed July 19, 2023).

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (U.S). Words Matter – Terms to Use and Avoid When Talking about Addiction. November 2021. (Accessed August 2, 2023).

- Bisanalli S, Nesargi S, Govindu RM, Rao SP. Kangaroo mother care in hospitalized low birth-weight infants on respiratory support: A feasibility and safety study. Adv Neonatal Care 2019;19(6):E21-25. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000666.

- Azevedo VM, Xavier CC, Gontijo Fde O. Safety of kangaroo mother care in intubated neonates under 1500 g. J Trop Pediatr 2012;58(1):38-42. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmr033.

- van Zanten HA, Havenaar AJ, Stigt HJH, Ligthart PAH, Walther FJ. The kangaroo method is safe for premature infants under 30 weeks of gestation during ventilatory support. J Neonatal Nursing 2007;13(5):186-90. doi: 10.1016/j.jnn.2007.07.002.

- Lorenz L, Dawson JA, Jones H, et al. Skin-to-skin care in preterm infants receiving respiratory support does not lead to physiological instability. Arch Dis Child-Fetal Neonatal Ed 2017;102(4):F339-44. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311752.

- Mori R, Khanna R, Pledge D, Nakayama T. Meta-analysis of physiological effects of skin-to-skin contact for newborns and mothers. Pediatr Int 2010;52(2):161-70. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2009.02909.x.

- Park HK, Choi BS, Lee SJ, Son IA, Seol IJ, Lee HJ. Practical application of kangaroo mother care in preterm infants: Clinical characteristics and safety of kangaroo mother care. J Perinat Med 2014;42(2):239-45. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2013-0066.

- Bera A, Ghosh J, Singh AK, Hazra A, Som T, Munian D. Effect of kangaroo mother care on vital physiological parameters of the low birth weight newborn. Indian J Community Med 2014;39(4):245-49. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.143030.

- Heimann K, Vaessen P, Peschgens T, Stanzel S, Wenzl TG, Orlikowsky T. Impact of skin-to-skin care, prone and supine positioning on cardiorespiratory parameters and thermoregulation in premature infants. Neonatology 2010;97(4):311-17. doi: 10.1159/000255163.

- Bohnhorst B, Gill D, Dördelmann M, Peter CS, Poets CF. Bradycardia and desaturation during skin-to-skin care: No relationship to hyperthermia. J Pediatr 2004;145(4):499-502. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.06.019.

- Bauer J, Sontheimer D, Fischer C, Linderkamp O. Metabolic rate and energy balance in very low birth weight infants during kangaroo holding by their mothers and fathers. J Pediatr 1996;129(4) 608-11. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70129-4.

- Gale G, Franck L, Lund C. Skin-to-skin (kangaroo) holding of the intubated premature infant. Neonatal Netw 1993;12(6):49-57.

- Ludington-Hoe SM, Ferreira C, Swinth J, Ceccardi JJ. Safe criteria and procedure for kangaroo care with intubated preterm infants. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2003;32(5) 579-88. doi: 10.1177/0884217503257618.

- Pandya D, Kartikeswar GAP, Patwardhan G, Kadam S, Pandit A, Patole S. Effect of early kangaroo mother care on time to full feeds in preterm infants – A prospective cohort study. Early Hum Dev 2021;154:105312. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2021.105312.

- Broge MJ, Steurer LM, Ercole PM. The feasibility of kangaroo care and the effect on maternal attachment for neonates in a pediatric cardiac intensive care unit. Adv Neonatal Care 2021;21(3): E52-e59. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000800.

- Levesque V, Johnson K, McKenzie A, Nykipilo A, Taylor B, Joynt C. Implementing a skin-to-skin care and parent touch initiative in a tertiary cardiac and surgical neonatal intensive care unit. Adv Neonatal Care 2021;21(2):E24-34. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000770.

- DiMenna L. Considerations for implementation of a neonatal kangaroo care protocol. Neonatal Netw 2006;25(6):405-12. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.25.6.405.

- Roark TH, DePriest D, Moore B, et al. Standardizing a method to safely perform kangaroo care for neonates while on high-frequency jet ventilation. Resp Care 2019;64(Suppl 10):3235709.

- Minot KL, Kramer KP, Butler C, et al. Increasing early skin-to-skin in extremely low birth weight infants. Neonatal Netw 2021;40(4):242-50. doi: 10.1891/11-T-749.

- Galligan M. Proposed guidelines for skin-to-skin treatment of neonatal hypothermia. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2006;31(5):298-304,quiz 305-06. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200609000-00007.

- Craig A, Deerwester K, Fox L, Jacobs J, Evans S. Maternal holding during therapeutic hypothermia for infants with neonatal encephalopathy is feasible. Acta Paediatr 2019;108(9):1597-1602. doi: 10.1111/apa.14743.

- Saptaputra SK, Kurniawidjaja M, Susilowati IH, Pratomo H. How to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of kangaroo mother care: A literature review of equipment supporting continuous kangaroo mother care. Gac Sanit 2021;35(Suppl1):S98-s102. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2020.12.037.

- Bollag L, Lim G, Sultan P, et al. Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology: Consensus statement and recommendations for enhanced recovery after cesarean. Anesth Analg 2021;132(5):1362-77. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005257.

- Weber A, Jackson Y. A survey of neonatal clinicians’ use, needs, and preferences for kangaroo care devices. Adv Neonatal Care 2021;21(3):232-41. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000790

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this position statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. Internet addresses are current at time of publication.

Last updated: Dec 3, 2024

Click on the image to open it in larger window