Practice point

Vascular anomalies in childhood: When to treat and when to refer

Posted: Aug 5, 2022

Principal author(s)

Kelley Zwicker, Julie Powell, Carl Cummings; Canadian Paediatric Society, Community Paediatrics Committee

Paediatr Child Health 2022 27(5):310–314.

Abstract

Vascular anomalies are heterogeneous diagnoses that affect blood and/or lymphatic vessels. Affected children may experience pain, functional loss, infection, coagulopathies, and psychological challenges. Diagnosis and management often warrant an interdisciplinary approach. There are seven vascular anomalies clinics in Canada that offer interdisciplinary care. This practice point outlines a treatment approach for the most common paediatric vascular anomaly (hemangioma). It reviews indications for referral to a specialized clinic, with focus on complex vascular anomalies, specifically infantile hemangioma, which can pose complications.

Keywords: Congenital hemangioma; Infantile hemangioma; Propranolol; Vascular anomaly

Background and prevalence

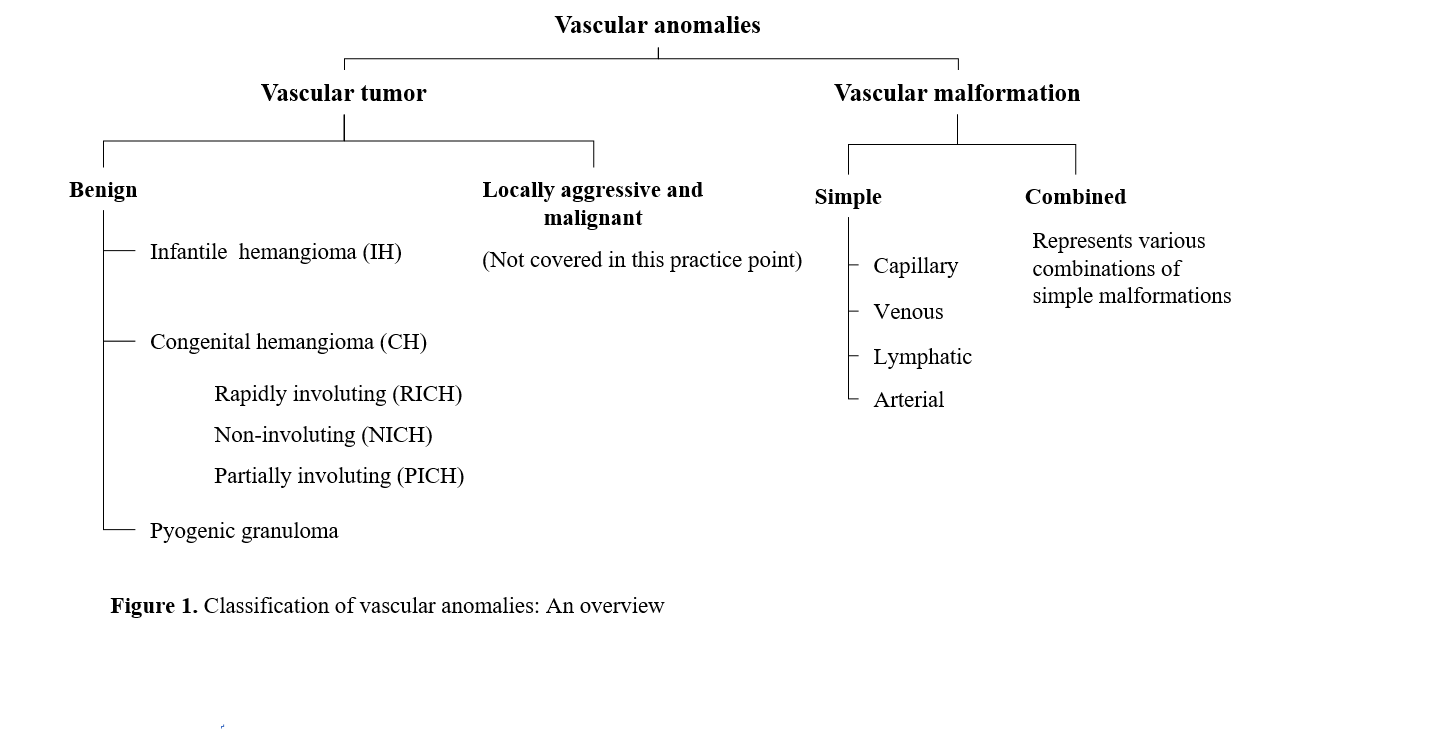

The classification system for vascular anomalies has been established by the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA). There are two groups: tumors (which are proliferative) and malformations (Figure 1) [1], which are defined by the anomalous vessel type (i.e., capillary, artery, vein, lymphatic). Historic terms such as “strawberry mark” and “port-wine stain” are discouraged (Table 1). ISSVA nomenclature facilitates improved communication among specialists who care for patients with these anomalies.

Hemangiomas affect an estimated 4% to 10% of infants [2]. Because hemangiomas tend to involute (“shrink”) spontaneously, there is often an assumption that they resolve without complication. However, up to 15% of hemangiomas can present with complications, mostly commonly ulceration, pain, permanent functional impairment, or negative cosmetic outcome [3]. Knowing the types of hemangiomas and their natural history is necessary for health care providers to counsel, help navigate patient or parent expectations, and appropriately manage these anomalies. Infantile hemangiomas (IH) and congenital hemangiomas (CH) are the focus of this practice point.

| ISSVA terms | Outdated terms |

|

Infantile hemangioma (IH) Congenital hemangioma (CH) |

Strawberry hemangioma Capillary angioma Cavernous hemangioma |

|

Capillary malformation/ Nevus flammeus |

Port-wine stain Capillary hemangioma |

| Lymphatic malformation |

Cystic hygroma Lymphangioma |

| ISSVA International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies | |

Infantile hemangiomas (IH)

IH (Figure 2) are much more common than CH (Figure 3). IH demonstrate a characteristic phase of growth and regression. The proliferative phase begins in infancy and often becomes noticeable in the first 4 weeks of age [4]. This phase is characterized by rapid growth during the first 1 to 3 months post-birth, with most continuing to grow between 5 and 12 months of age, followed by a plateau phase that typically occurs between 12 to 18 months of age. The involution phase occurs between 1 to 7 years of age, and recent studies indicate that 90% of IH will stop involuting by 4 years of age. Approximately 50% of untreated IH leave residual fibro fatty tissue, atrophy, scars and/or redundant skin, with or without telangiectasias [5][6].

Complicated IH were historically treated with systemic steroids [2], but this approach has fallen from favour due to their side effects and discovery in 2008 of the efficacy—and better safety profile—of oral beta-blockers, which are now considered as first choice for treatment. Laser treatment may be an option, but this procedure is typically reserved for ulcerated hemangiomas that are unresponsive to beta blockers, or for residual telangiectasias present after involution. There are no Canadian consensus guidelines for IH treatment, although it is well established practice worldwide to use oral beta-blockers for complicated or at-risk IH. Indications for starting propranolol for IH include: function- or life-threatening IH such as airway compromise, periocular IH, lip or nasal location (especially nasal tip), auditory canal involvement, ulceration, segmental hemangiomas of the face, or IH with risk of permanent disfigurement [2][7][8].

In Canada there is a Health Canada-approved propranolol formulation called Hemangiol. Two published guidelines recommend starting propranolol at 1 mg/kg per day, administered as a divided dose two times daily [2][7]. The dose is then escalated weekly by 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day, administered as a divided dose two times daily up to 2 to 3 mg/kg/day [9]. Slower dose increases are suggested for neonates, premature infants <2 months corrected age (CA), or in cases with suspected PHACE syndrome (a large segmental IH on the face or neck associated with any one of the following: Posterior fossa, Hemangioma, Arterial anomalies of the brain or the neck, Cardiac/coarctation, or the Eyes) [10]. Adjusting the dose for increasing weight is recommended.

Before starting propranolol, examination of cardiac rhythm, murmur, abnormal heart sounds, and peripheral pulses should be completed. A pre-treatment electrocardiogram (ECG) and echocardiogram should be considered when the cardiac exam is abnormal. In some centres, heart rate and blood pressure are measured at baseline for 1 to 2 h after the first dose, and after each dose increase. This practice is centre-dependent. Inpatient initiation of propranolol is recommended for infants with cardiorespiratory comorbidities, infants <5 weeks of age, and families with suboptimal social support [2]. Routine follow-up for patients on a stable dose without complications typically occurs every 2 to 3 months, but is also centre-dependent.

Common side effects of propranolol treatment are sleep disruption and coolness or mottling of the hands and feet. Other less common effects include hypotension, bronchospasm, hypoglycemia, bradycardia, and hyperkalemia. Absolute contraindications to propranolol include hypoglycemia, second- or third-degree heart block, and hypersensitivity to propranolol [2][7][8]. Hypoglycemia is a serious potential complication. Counselling parents to administer the dose around feeding time, morning and evening, and to recognize the symptoms of hypoglycemia (e.g., sweating, tachycardia, appearing anxious or jittery), is recommended. Spontaneous hypoglycemia has been observed after large dose changes or especially when propranolol is not stopped during an illness. Holding propranolol during illness is recommended due to the risks of reduced oral intake and dehydration.

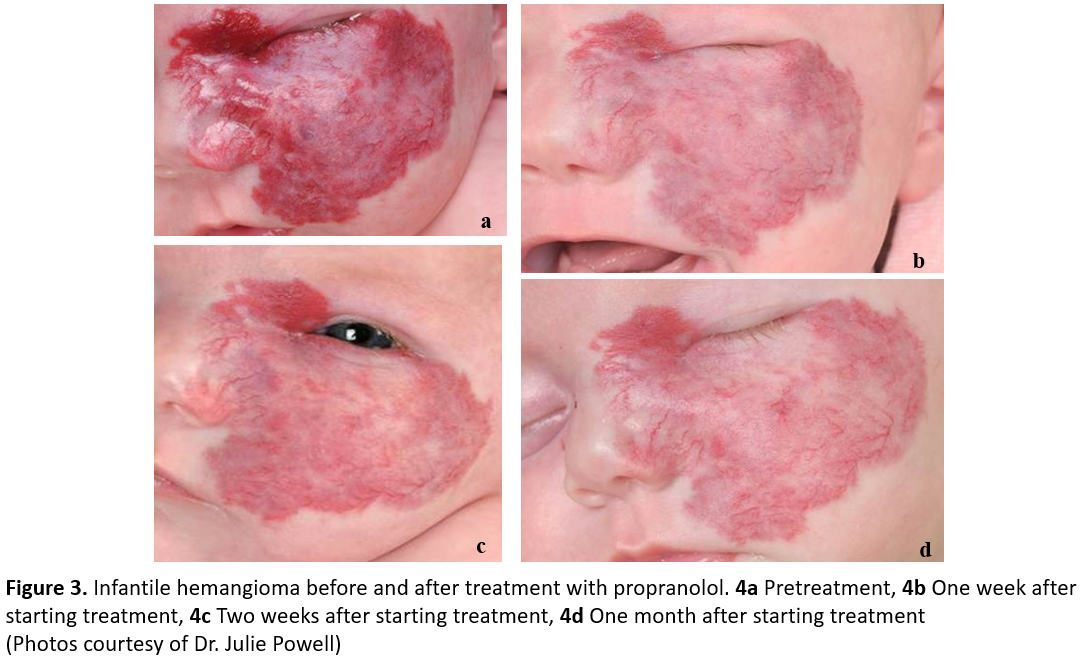

Propranolol is typically continued for at least 6 months, but initial response generally occurs within 3 to 4 weeks of starting treatment. A visible colour change is often observed in the first 48 h of treatment (Figure 3). Indications for treatment cessation include involution of the lesion or lack of response. Parents should be counselled that in some cases, rebound growth might occur after discontinuing medication [11]. Parents should also be advised that the hemangioma may not resolve completely, and that residual fibrofatty tissue, atrophy, and/or telangiectasias may persist.

A number of clinical trials have evaluated topical Timolol to treat IH [12]. Timolol may be an option for small, thin IH, and is prescribed as Timolol maleate 0.5% ophthalmic gel-forming solution. One to two drops are administered twice per day, regardless of the size of the hemangioma. The pharmacokinetics of Timolol is not well understood, and the timing to peak serum levels is unknown with cutaneous application. More drops should not be prescribed for bigger lesions. Also, topical application to an ulcerated hemangioma may not be safe, because of a greater absorption. For a large or ulcerated IH, treatment with oral propranolol is preferable to cutaneous Timolol.

Congenital hemangiomas (CH)

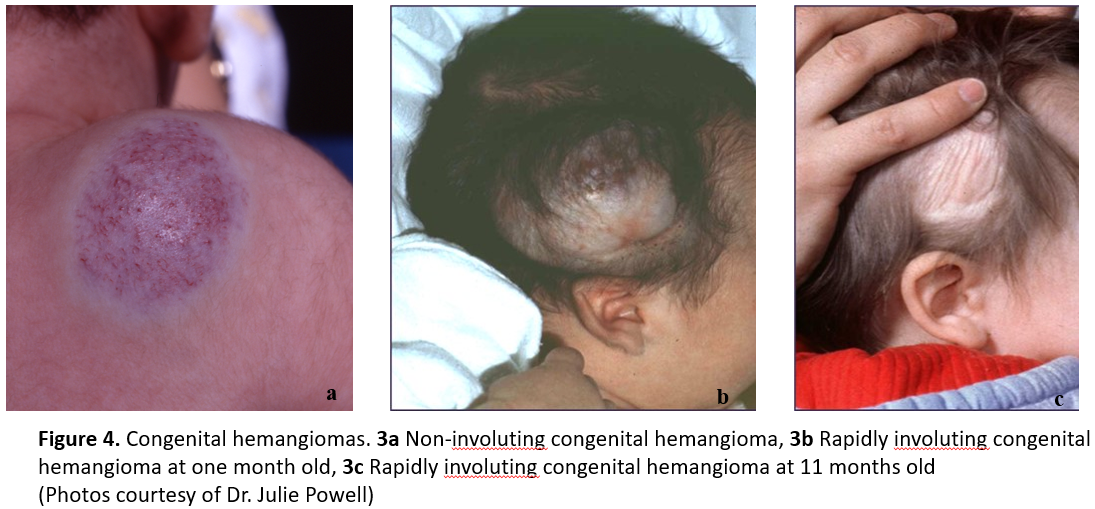

CH are distinct from IH (Figure 4) because they are fully developed at birth [1]. CH must be differentiated from IH, which are occasionally present at birth as a vascular stain, telangiectasias, or bruise-like lesion, but more typically grow in the first weeks to months of life. CH present at birth as vascular plaques or tumors that do not show early proliferation [13]. The three major subtypes of CH are: rapidly involuting congenital hemangioma (RICH); non-involuting congenital hemangioma (NICH); and partially involuting congenital hemangiomas (PICH) [14] (Figure 4). CH do not respond to steroids or beta-blockers, and current evidence does not support use of beta-blockers to treat of NICH or PICH specifically. Treatment for RICH is not generally indicated due to their rapid spontaneous involution. When CH are ulcerating or pose a cosmetic or functional risk, refer the infant to a vascular anomalies clinic or paediatric dermatologist.

When to treat and when to refer

Hemangiomas that are small, not ulcerating, and not located in a cosmetically sensitive area can often be treated without referral. Referral is recommended for hemangiomas affecting the eye, nose, urethra, anus, or liver, and for large facial hemangiomas. If more than five cutaneous hemangiomas are present, consider an abdominal ultrasound for associated hepatic hemangiomatosis. Evaluate all large, segmental facial infantile hemangiomas for PHACE associations. Early treatment helps ensure optimal outcome. Refer more complex cases as soon as possible and, ideally, before 4 months of age.

Ulcerations occur in about 15% of IH, especially during the rapid growth phase. Healing time is difficult to predict. Pain and infections are frequent complications that need to be rapidly addressed, and timely referral is encouraged. When any hemangioma is affecting or impinging on a critical structure, treatment is preferable to ‘watchful waiting’. Also refer young patients who experience adverse effects from, or do not respond to, propranolol treatment. For these cases, other oral beta-blockers (Nadolol or atenolol), oral steroids or, rarely, a surgical resection may be needed. Treatments are not always curative, but they can address function and esthetics.

Other vascular anomalies are characterized within the ISSVA classification and need to be differentiated from IH. Capillary malformations are congenital flat pink-to-red stains [1] that can occur anywhere on the face or body. Venous malformations (VM) are abnormal veins with a defective smooth muscle cell layer. Blood flows slowly, with a tendency to phlebolith formation and discomfort. Arteriovenous malformations (AVM) are abnormal connections between arteries and veins that lack capillary beds. Lymphatic malformations are characterized by their size (microcystic or macrocystic), with a macrocystic anomaly of the neck being one variant. Overgrowth syndromes (e.g., PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum [PROS]) are also associated with vascular anomalies. These more complex cases require referral to a vascular anomalies clinic. Current treatment options for vascular malformations are diverse, and include conservative measures (pain relief, compression garments), interventional procedures (sclerotherapy, surgery), or a combined approach. Recent targeted medications to treat complex vascular malformation (e.g., sirolimus) are promising but beyond the scope of this practice point.

Key practice points for care of IH and CH in children

- Essential care for any hemangioma includes a complete physical and dermatological exam, and consideration of differential diagnoses. Proactively addressing parent and patient psychosocial concerns is encouraged.

- Not all hemangiomas require treatment. Indications to start treatment include vital or functional risk, location and impact on cosmesis, and ulceration.

- Early treatment is necessary for optimal outcome, and referrals should be made as soon as possible, ideally before 4 months of age.

- Use of appropriate terminology facilitates communication with parents of children affected and among specialties involved in managing paediatric hemangioma.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Drs. Elena Pope (Section Head, Paediatric Dermatology, SickKids) and Miriam Weinstein (Staff Physician, Paediatric Dermatology, SickKids) for reviewing this practice point, which was also reviewed by the Canadian Paediatric Society’s Drug Therapy and Hazardous Substances Committee.

CANADIAN PAEDIATRIC SOCIETY COMMUNITY PAEDIATRICS COMMITTEE (2019-2020)

Members: Julia Orkin MD (Chair), Marianne McKenna MD (Board Representative), Tara Chobotuk MD, Michael Hill MD, Audrey Lafontaine MD, Alisa Lipson MD, Carl Cummings MD (Past Chair), Larry Pancer MD (Past Member)

Liaisons: Peter Wong (Community Paediatrics Section Liaison)

Principal authors: Kelley Zwicker MD, Julie Powell MD, Carl Cummings MD

References

- Mulliken JB, Burrows PE, Fishman SJ, eds. Mulliken and Young’s Vascular Anomalies: Hemangiomas and Malformations. New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press; 2013.

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al. Clinical Practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics 2019;143(1):e20183475.

- Chamlin SL, Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, et al. Multicentre prospective study of ulcerated hemangiomas. J Pediatr 2007;151(7):684-89,689.e1.

- Tollefson MM, Frieden IJ. Early growth of infantile hemangiomas: What parent’s photographs tell us. Pediatrics 2012;130(2):e314-20.

- Chen TS, Eichenfield LF, Friedlander SF. Infantile hemangiomas: An update on pathogenesis and therapy. Pediatrics 2013;131(1):99–108.

- Liang MG, Frieden IJ. Infantile and congenital hemangiomas. Semin Pediatr Surg 2014;23(4):162–67.

- Solman LM, Glover M, Beattie PE, et al. Oral propranolol in the treatment of proliferating infantile haemangiomas: British Society for Paediatric Dermatology consensus guidelines. British Journal of Dermatology 2018;179(3):582–89.

- Martin K, Blei F, Chamlin SL, et. al. Propranolol treatment of infantile hemangiomas: Anticipatory guidance for parents and caretakers. Pediatr Dermatol 2013;30(1):155–59.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Hoeger P, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of oral propranolol in infantile hemangioma. N Engl J Med 2015;372(8):735-46.

- Garzon MC, Epstein LG, Heyer GL, et al. PHACE syndrome: Consensus-derived diagnosis and care recommendations. J Pediatr 2016;178:24-33.e2.

- Shah SD, Baselga E, McCuaig C, et al. Rebound growth of infantile hemangiomas after propranolol therapy. Pediatrics 2016;137(4):e20151754.

- Püttgen K, Lucky A, Adams D, et al. Topical timolol maleate treatment of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics 2016;138(3): e20160355.

- North PE, Waner M, James CA, Mizeracki A, Frieden IJ, Mihm MC. Congenital nonprogressive hemangioma: A distinct clinicopathologic entity unlike infantile hemangioma. Arch Dermatol 2001;137(12):1607-20.

- Nasseri E, Piram M, McCuaig CC, Kokta V, Dubois J, Powell J. Partially involuting congenital hemangiomas: A report of 8 cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;70(1):75–79.

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this position statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. Internet addresses are current at time of publication.

Last updated: Feb 8, 2024